Treasuring a closet of her own

A deeply personal exhibit at the Skirball showcases one woman’s journey toward personal freedom.

Seven bras. Twelve T-shirts. Thirteen pairs of socks. One robe. Two nightgowns. Thirteen blouses. Nine pairs of shoes. Six sweaters. Seven hats.

These items, along with an unspecified number of slacks, made up the entirety of Sara Berman’s wardrobe when she died peacefully at age 84.

Another thing should be noted about Berman’s clothing: It was all white, and each item was meticulously starched, ironed and folded before being put in its place.

Berman was the mother of author and illustrator Maira Kalman and the grandmother of curator and designer Alex Kalman, who together re-created a most intimate space as an exhibit titled “Sara Berman’s Closet,” on view at the Skirball Cultural Center through March 10.

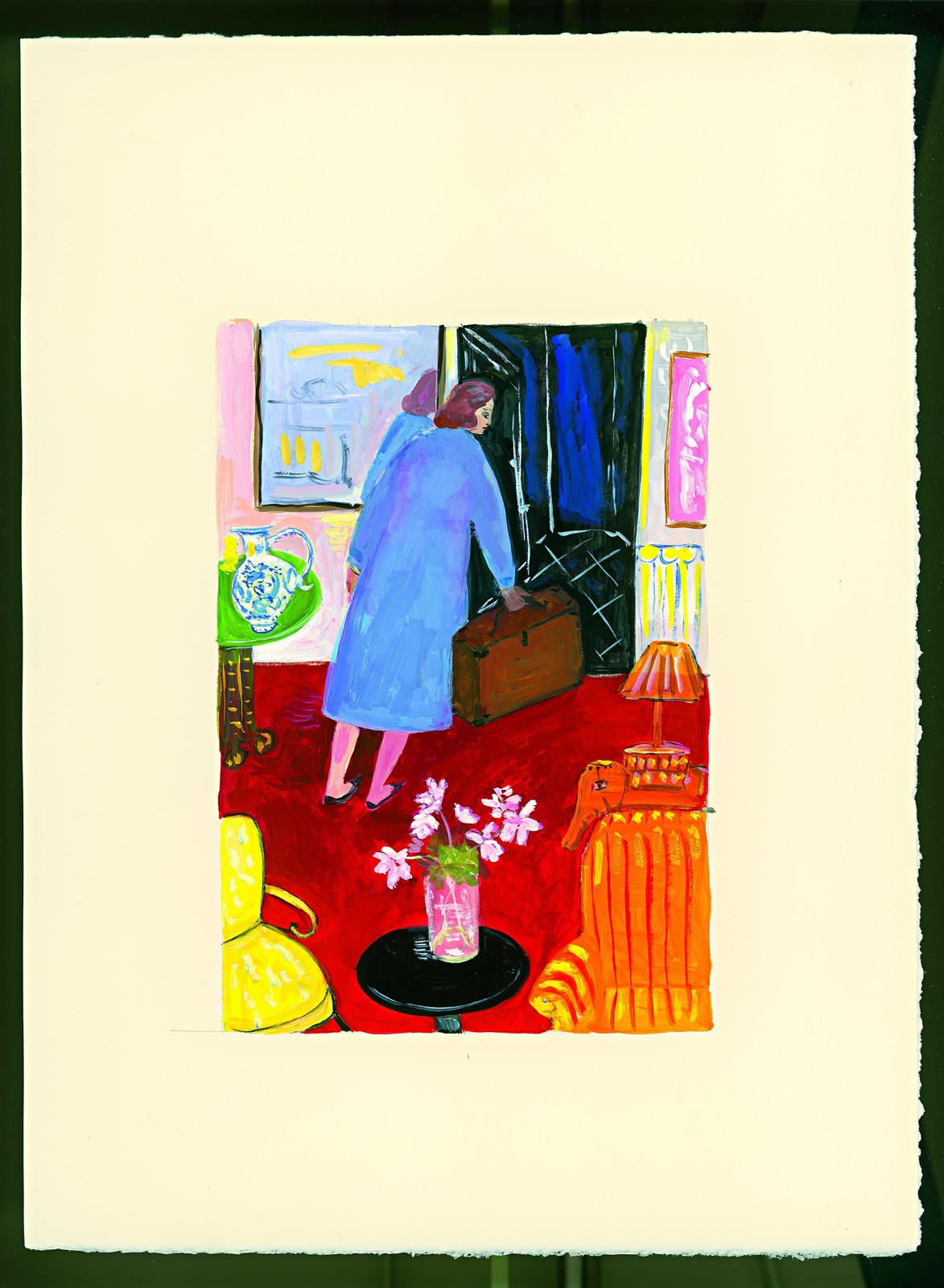

The exhibition coincides with the release of a book by the same name, featuring original text by the Kalmans and illustrations by Maira. Twelve original paintings from the book will be displayed alongside the installation.

“It was never about being overly fastidious. It was about a love of beautiful things,” Maira said of her mother’s immaculate boudoir. “That was part of Sara’s persona, and when she died we stood in her closet and said, ‘This should be an exhibit.’ ”

Ten years later the Kalmans opened the first incarnation of the installation at Mmuseumm, Alex’s Tribeca space — a freight-elevator shaft in a graffiti-ridden alley. It was a token of the richness of city life left for passersby to stumble upon and wonder about. There was little context. A plaque invited those intrigued by the humble, tidy closet to call a number to hear more about what they were seeing.

It wasn’t just a re-creation of one woman’s closet. It was a testament to the power of an individual life. It was a monument to freedom and self-expression, a paean to feminism and a meditation on what makes us human, how we cope with adversity and the ways in which we persevere.

People found the installation mesmerizing, Alex said by phone, precisely because it had been a real closet and not a premeditated work of art. Had it been created by artists as an artistic statement, it wouldn’t be nearly as interesting, he said.

When the installation closed at Mmuseumm, it made the auspicious leap — much to the Kalmans’ amazement — to the American Wing of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, where it was placed adjacent to another period piece: the elaborate dressing room of the richest woman in late-19th century America, Arabella Worsham, a Southern belle who married railroad magnate Collis Huntington.

The juxtaposition of unimaginable wealth and luxury with self-imposed austerity and restraint might have looked odd at first glance, Maira said, but it actually made quite a bit of sense. Both women were extremely powerful, just in different ways.

Berman found power in deeply personal choices. Born in Belarus in 1920, Berman lived a fairly idyllic life with her large family, including her favorite sister, Shoshana. The children frolicked in forests of wild blueberries, ate cake, and sang and danced to their hearts’ delight.

When Berman was 12, her family moved to Palestine, where she grew into a ravishing young woman. Despite what the Kalmans describe in the book as “terrible misgivings,” she married, moved to New York and had two daughters, including Maira.

It was not a happy marriage, and when the daughters grew up, the couple returned to Tel Aviv. Then, at age 60, Berman took a single suitcase and left her husband. She returned to New York City and found a small studio apartment in Greenwich Village. This, Maira said, was Berman’s liberation.

She thrived as a single woman in the city. She developed habits and joys all her own. She loved Fred Astaire, devoured autobiographies, regularly visited the Museum of Modern Art, ate herring and watched “Jeopardy” every night.

At some point, in what the book calls a “burst of personal expression,” Berman decided to wear only white. The clothes she kept from then on are the ones that can be found in the installation bearing her name.

The Kalmans are clearly a close family, and their love of Berman is palpable.

Their installation, however, is not sentimental.

“This is not a shrine,” said Maira, adding that although it is heartfelt and has quite a bit of emotional content, it is meant to be forward-thinking and inventive.

Alex agreed. The purpose of the installation, he said, is to elevate Berman’s life story into a set of values that people can connect to or find meaning in.

“It was just how she was living her life, and that is also what is so powerful about it,” he said. “It’s not coming from a place of self-consciousness or public presentation.”

Then there is the more personal meaning for the family. Alex and Maira consider “Sara Berman’s Closet” to be the work of three generations.

“It doesn’t feel like Maira and I are making something about Sara because Sara really made it,” he said. “I really feel like it’s a collaboration between Sara, Maira and myself.”

If one ponders the perfectly pressed whites of that diminutive Greenwich Village closet — imagining Berman alone in her apartment carefully starching and pressing her few belongings, thinking of the books she is reading and the glorious visits to the museum she plans to make — one can feel the inspiring resonance of a private life lived to its fullest potential and the remarkable spirit of a woman, who at age 60, finally found peace in a room of her own.