A long wait for artistic works’ liberation

New Year’s Day brought a vast bounty of artistic and culturally important works into the public domain for the first time.

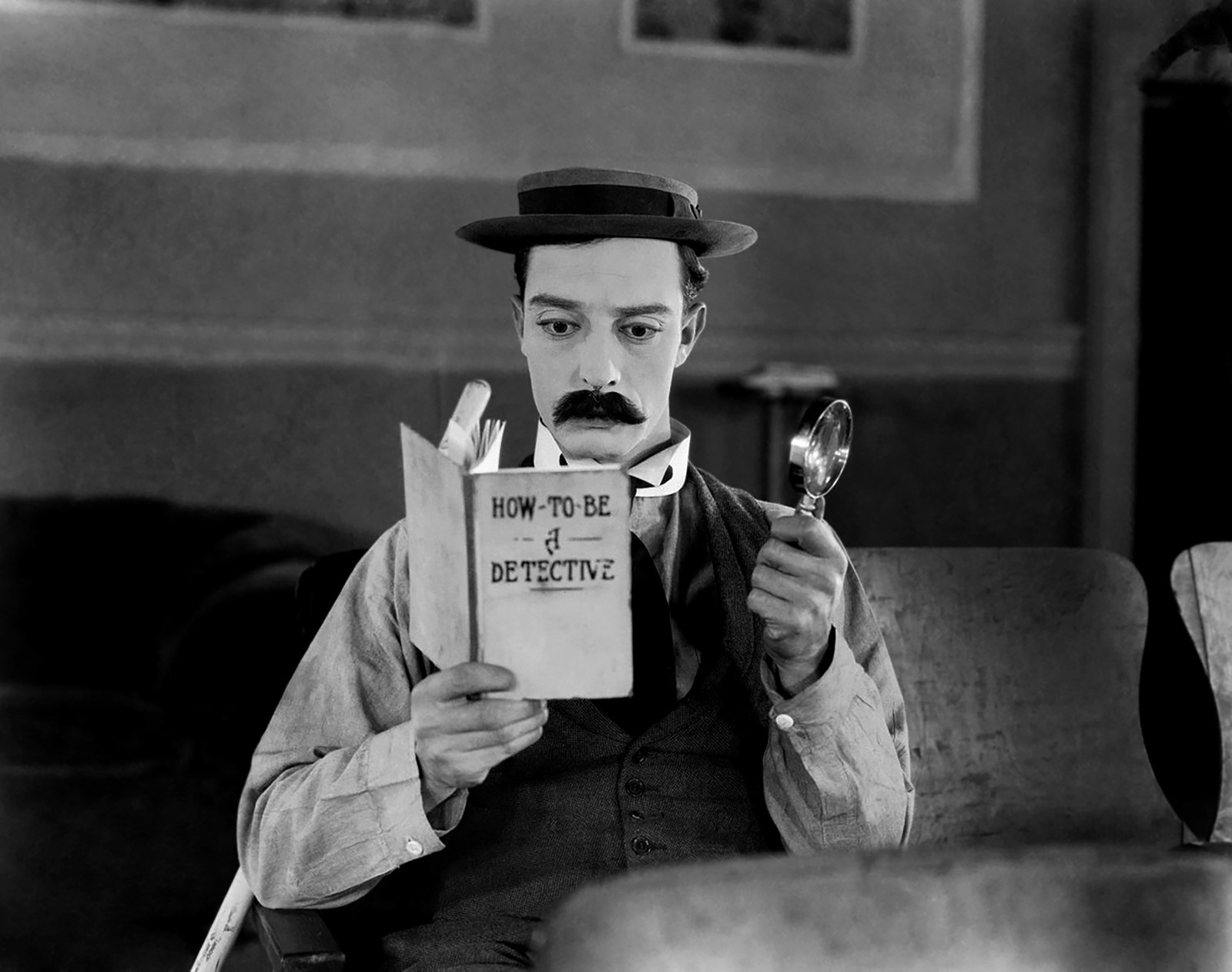

Among the classic works that can now be reproduced, reprinted, performed or shown by anyone without interference from heirs of their creators or the payment of license fees are George Gershwin’s “Rhapsody in Blue” and “Fascinating Rhythm,” E.M. Forster’s novel “A Passage to India,” A.A. Milne’s poetry collection “When We Were Very Young” (including the first appearance of Winnie-the-Pooh) and Buster Keaton’s film “Sherlock Jr.”

Because all were produced in 1924, they finally reached the end of their copyright period under the 1998 Sonny Bono Copyright Term Extension Act, through which Congress extended their protection for another 20 years beyond the previous rule.

This year’s haul is the second to reach the public after the 20-year freeze imposed by the act; New Year’s Day 2019 had gifted us with free access to Cecil B. DeMille’s film “The Ten Commandments,” Robert Frost’s “Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening” and the song “Yes! We Have No Bananas,” among other works published or created in 1923.

The liberation of all these creations, however, should also be an occasion for mourning. They would have been released to the public domain in the early 1960s, if not for an aggressive campaign staged in Washington by big media companies, especially Walt Disney Co., desperate to keep control of their copyrighted works for as long as possible.

Copyrights prevent consumers or creators from accessing, building on, or even repurposing artistic works without the permission of the copyright holders or the payment of a fee that can be steep. That’s arguably an obstacle to cultural development, and raises the question of why the heirs should exercise so much power and collect such payouts so many decades after the creators are gone.

As was well documented in the run-up to the 1998 law, Disney’s concern was that “Steamboat Willie,” the first short featuring Mickey Mouse, was facing copyright expiration in 2003, which could mean Disney’s losing copyright control over Mickey Mouse generally. The company deployed its lobbying clout and campaign contributions to stave off the loss. The short now won’t enter the public domain until 2023, or 95 years after it was first shown.

Let’s examine the context of the 1998 act and of copyright rules generally. Congress derives its authority to set copyright terms from the Constitution, which allows it to promote science and art by granting “for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries.”

Obviously the idea is to provide incentive for writing and invention without indefinitely foreclosing the free dissemination of the work to the public. The debate has always been how long should a “limited time” be?

The arguments mustered for longer copyrights in 1998, and on behalf of earlier legislation extending copyright, fell into three categories. One was that material in the public domain would be under-exploited — no one would republish a public domain work because there was limited prospect of profit. The second was that material in the public domain would be over-exploited — too many unauthorized versions would sap public domain works of their market value.

The third was that public domain works would lose their value from misuse. What sort of misuse? As copyright expert Paul J. Heald observed, “The entire debate seems to turn on the effect of having unauthorized porn movies starring Mickey Mouse or Superman.”

But some managers of copyrighted works had other concerns. The Gershwin Family Trust, for instance, fretted that if copyright eliminated its power to control presentations of the composer’s work, “Someone could turn ‘Porgy and Bess’ into rap music.”

Who’s to say that would be bad, given that the Gershwin opera drew freely from black and Southern culture in the first place, and that reimagining a work such as “Porgy and Bess” can be an expression of cultural evolution years after its original creation?

Clearly, at least two of these arguments are mutually contradictory — that works could be underused and overused. Heald and his colleagues tested all three, using sales of audiobooks of public domain and copyrighted works as proxies, and found no pattern validating any of the arguments. The real motivation, plainly, was keeping financial control over works with residual popularity.

Since the passage of the 1998 act and even before it, copyright owners have sought ways to circumvent expiration. In 2013, the estate of Arthur Conan Doyle tried to block new uses of Sherlock Holmes, who first appeared in print in 1897. Its argument was that Holmes and Watson should remain under copyright until the last original work in which they appeared entered the public domain, which would not happen until 2023.

The estate’s goal was to block an anthology of freshly written stories featuring the characters. But it lost in U.S. federal court, which ruled that the characters did not have an independent life after the first story’s copyright expired.

Other peculiarities exist. Emily Dickinson died in 1886, but the copyright to many of her poems remains in the hands of Harvard University Press, thanks to claims based on the date and nature of emendations made to the poems by various editors over time.

Disputes over how copyright holders manage their forebears’ works also bubble up from time to time. In 2018, Martin Luther King Jr.’s son Dexter, who manages the rights to the civil rights leader’s speeches, licensed a 1968 sermon to Ram trucks, even though the sermon’s theme was the downside of commercialization in society. The incident caused an internal dispute within the family. (King’s most notable speech, the “I Have a Dream” speech at the 1963 March on Washington, won’t enter the public domain until 2058.)

That brings us to the issue of what’s been kept out of the public domain by the 1998 law. Works from 1963 would now be available, including “I Have a Dream,” Alfred Hitchcock’s film “The Birds,” Maurice Sendak’s children’s classic “Where the Wild Things Are” and Betty Friedan’s “The Feminine Mystique.” Instead, they’ll still be controlled by their creators’ heirs for another 28 years.

Aficionados of film, literature, and music will have to wait another year for the next trove. Jan. 1, 2021, will bring us unfettered access to “The Great Gatsby,” DuBose Heyward’s novel “Porgy,” the source of Gershwin’s opera, and works by P.G. Wodehouse, Edith Wharton, and Ernest Hemingway; Charlie Chaplin’s film “The Gold Rush”; and “Always” by Irving Berlin.

Can’t wait.