Column One

Falling through a tattered safety net

One man’s mental illness takes a toll on him and his siblings, some who work in a system that’s failed him

She had rushed from a lunch engagement still wearing a silky flowered dress. She sat on a curb beside her 45-year-old brother in the trash area of a Pasadena strip mall. She made small talk, easing into the big question: Would he let her take him back to his home?

If he didn’t go, he would soon be picked up on a warrant. He was AWOL from his court-supervised diversion program.

Sympathetic social workers had helped Sarah Dusseault find her brother after he left his residential care facility in South Los Angeles and walked back to old haunts in Pasadena. Dusseault, who is a prominent figure in local government efforts to help the homeless, had pleaded with them to commit him on a 72-hour psychiatric hold under the standard of grave disability.

They said they were hamstrung because he appeared well clothed and fed.

“The whole thing drips with irony,” Dusseault said. “I just went out there and gave him clean clothes and gave him lunch. Are you saying I should make sure I don’t give him anything? Is that the better plan?”

She lined up a shelter and came back a couple of days later to pick him up. But he wasn’t cooperating. He ignored the question and talked about his fantasy of working with Antonio Banderas. Then his voice stopped while his lips continued to shape words.

“Are you talking to Ben?” she asked.

A minute later he was on his feet, marching in a circle while ranting out loud to, or about, his younger brother Ben.

She had failed.

By keeping tabs on the sheriff’s inmate locator website, she learned two days later that her brother was back in the mental ward at L.A. County’s Twin Towers jail. His next home would likely be state prison where, as a registered sex offender, his safety would be in jeopardy.

“If he goes to prison, he’ll die,” Dusseault said. She knew she had to do everything possible to prevent that.

b

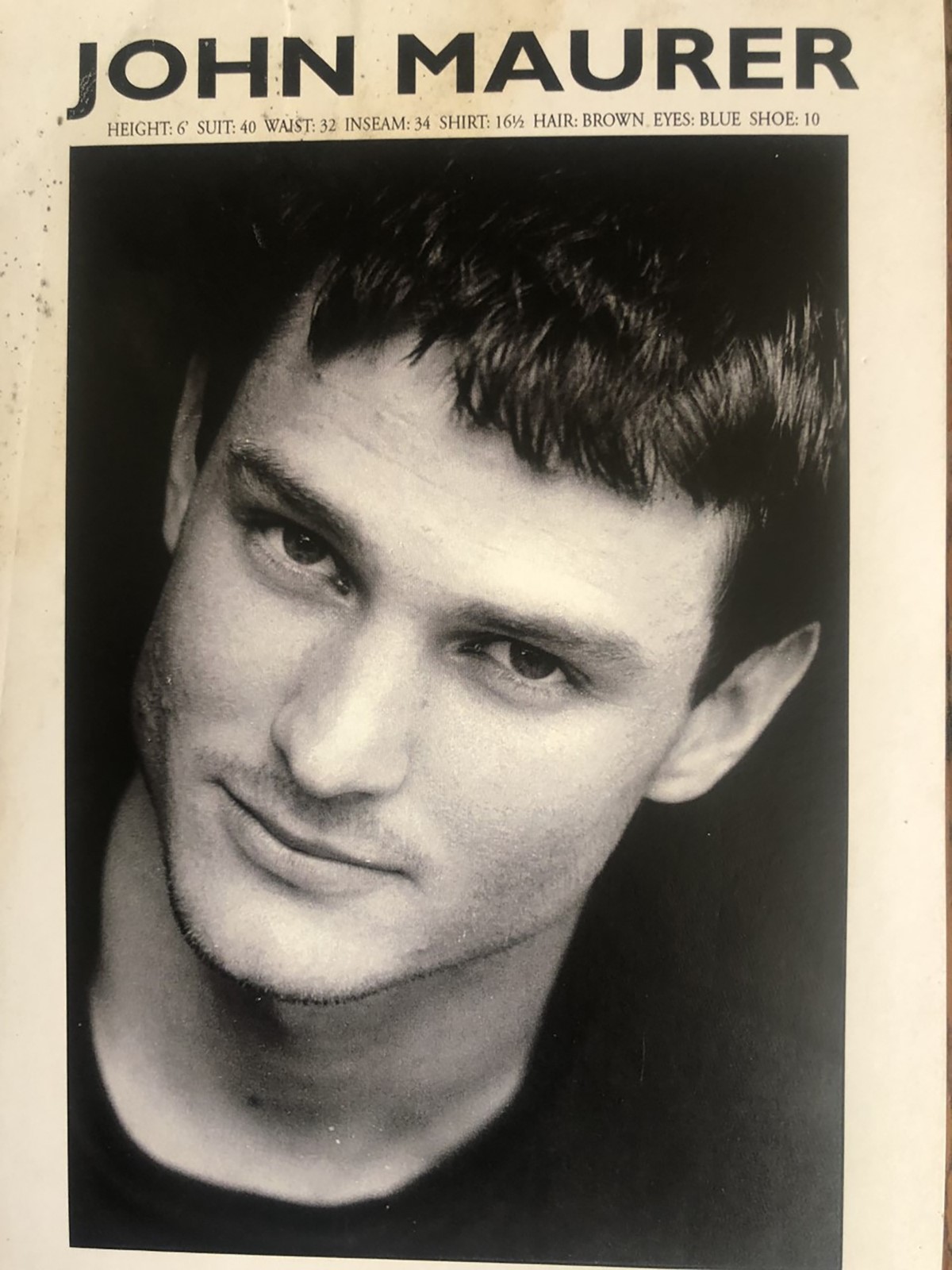

John Samuel Maurer, 10th of 11 brothers and sisters, was an intelligent, charming and handsome college student when the first cracks in his winning personality began to show. While his sister Sarah was rising to prominence in Los Angeles political circles and brother Steve was advancing in the medical ranks at Patton State Hospital, John was descending into a vortex of mental illness, caroming from one placement to another, slipping through virtually every institution in a safety net so tattered that not even his accomplished siblings could make it work.

And if they couldn’t help, what chance is there for people whose relatives lack such connections?

There are thousands of others like John Maurer, whose mental illness, compounded by drug use, keeps them in a cycle of homelessness, hospitalization and jail.

A recent academic study found that at least 1 in 5 people engaged by outreach workers in L.A. County — about 7,000 — had a diagnosis of serious mental illness.

The nexus between mental illness and low-level crime means that L.A. County Jail is the treatment option of last resort. On a typical day, almost 40% of the jail population — about 5,000 inmates — are in need of mental health treatment, many waiting for months to regain competence to stand trial.

In L.A. County’s mental health system there are only about 1,700 beds in what are called sub-acute facilities, where patients can stay for a few days or months with psychiatric care. That’s about a third of the estimated number needed, which means there are roughly three mentally ill people in jail and four on the streets for every one receiving extended clinical care.

Because those beds are always full, hospitals that receive patients committed on psychiatric holds have few options for follow-up care, distorting the entire system. Clinicians are reluctant to take people off the street, knowing they will likely only be released after the 72-hour limit. Patients released without treatment are often picked up again and again on new psychiatric holds.

“The state is using lots of involuntary holds that seem to add up to nothing more than more involuntary holds,” wrote researcher Alex Barnard of the New York University Department of Sociology in an upcoming report on California’s conservatorship practices.

Any treatment Maurer has received is hidden behind a shield of privacy laws. While his criminal cases are recorded in electronic files for anyone to see, not even Maurer’s family members know definitively how many times he’s been checked into hospitals on psychiatric holds.

By piecing together what they know, however, they’ve drawn a sad parallel. John’s hospital stays most likely outnumber his trips to jail but were far shorter in duration and just as likely to end badly.

When John was convicted of his first criminal offense in Los Angeles County — an August 2000 charge of disorderly conduct — he was 24 and had emerging indications of his schizophrenia. But it would take another 14 years, probably more than a dozen psychiatric holds and at least 10 more criminal convictions in L.A., San Bernardino and Riverside counties before the court system would commit him to a conservatorship, its most powerful tool to help repeat offenders whose crimes result from mental illness. And then things only got worse.

John had spent those years in the homes of his parents in Arizona, a sister in Sierra Madre or a brother in Yucaipa, eventually wearing all of them out by stealing money, disappearing on cross-city walks or acting so bizarrely that they would have to check him into a hospital.

“We’ve taken him to so many hospitals, they’re all jumbled together,” his brother Steve said in an interview.

For a time he lived in Steve’s guest house and was taking medication.

“He was doing better,” Steve said. “Helped us build a deck. I paid him.”

Then he found a source for drugs. He started poking holes in the wall with a pool cue and urinating on the furniture. Steve took him to a treatment center in Cabazon, but he would not go in. He crouched outside all night, then disappeared. Steve spotted him months later at a gas station.

“He looked outlandish,” Steve recalled. “Heavy coat on a hot day, shorts, red burnt skin. He had been wandering in the desert near Cabazon and Beaumont.”

It was a bright red flag that the system missed. Steve isn’t clear what happened after that. The episode blended into all the others. Maybe that was the time he took John to a Moreno Valley hospital. The hospital admitted him but called Steve a few days later to pick him up.

“How is he?” Steve asked. The nurse on the phone said HIPAA, the federal patient privacy law, prohibited her from saying.

“That’s fine, you keep him,” Steve said in frustration.

A charge nurse came on the phone and explained that John had already been released with a bottle of medication but would not leave the patio area.

“We went and picked him up,” Steve said.

b

Court records show that John was arrested in 2007 for being drunk in public. After he broke into an abandoned house in 2008, he was determined to be mentally incompetent to stand trial and was sent to Patton State Hospital for the mentally ill near San Bernardino. Steve, then chief of staff there, had him transferred to Metropolitan State Hospital in Norwalk to avoid a conflict. John was declared to have regained his competency, returned to the trial court for conviction and released.

Then he ended up at Community Hospital of San Bernardino, where a doctor who knew Steve proposed filing a petition to place John under a conservatorship, a procedure under state law that would give a public guardian almost total control over John’s life, with the power to place him in a locked facility and force him to take medication.

As a protection for those whose rights it abridges, the conservatorship law, known for its authors as Lanterman-Petris-Short, requires the court to find evidence of grave disability meeting the criminal standard of proof — beyond a reasonable doubt. The court rejected the petition.

“I gathered it was financial,” Steve said. “The county has to pay. That’s why they do not want to do it.”

Through much of that turmoil, John pined for a normal life — marriage, home and family. But by 2014, his sister Sarah Dusseault saw that John’s hopes for a regular life had died and along with it any value in keeping it within the family.

Dusseault, who had been L.A. Mayor James Hahn’s homelessness and housing deputy and was soon to be appointed by Supervisor Hilda Solis to the governing commission of the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority, bared her personal anguish in an op-ed published by The Times early in 2014.

“In my professional life, I have worked to build housing and create programs to end homelessness,” she wrote. “But the system is broken, especially for homeless people with severe mental illness, like my brother. My family and I just keep hitting dead ends trying to get him help.”

Two days after publication, John was arrested in West Covina for vandalism and trespass.

Dusseault hired an attorney and filed a petition to have John placed under a conservatorship. In February of 2014, a judge in L.A. County’s mental health court found John gravely disabled and placed him in the care of the public guardian.

The conservatorship — one of many interventions that John’s family hoped would be his salvation — either came too late, ended too early or was predetermined to fail because of the inadequacy of the treatment options for someone like him.

“It’s a godsend because it’s a placement,” Dusseault thought when John’s public guardian had him transferred from jail to a locked residential program in Pico Rivera.

“Initially John was enthusiastic,” Dusseault said. “‘I’m going to stay clean. This is so fun.’”

His brothers and sisters could visit and even take him on weekend furloughs.

But problems became apparent. The severe shortage of beds in locked, long-term institutions for the mentally disabled meant that John’s home would be out of the way for both his siblings whose high-pressure careers made visits difficult to schedule.

“The placements are not about where this person grew up or family is,” Dusseault said. “If he isn’t in regular contact with me or one of the other siblings he starts to deteriorate. He needs that family support.”

It also turned out that a drug dealer was working right outside its doors.

“He eventually started taking meth there,” Dusseault said.

He got into a fight and was sent to jail. After that she heard through the grapevine that he was hospitalized again, probably more than once. But she did not know where or for how long.

Two years later, John’s conservatorship was summarily ended without any of John’s siblings being notified or even knowing at the time where he was.

The conservatorship law has an automatic sunset after one year unless evidence is presented that the person is still gravely disabled. In practice, that evidence comes from a private psychiatrist who must spend a day in court waiting for a hearing that is often scheduled hours before it actually occurs. As often happens, John’s psychiatrist did not show up, leaving the court no choice but to end his conservatorship.

It was a turning point of sorts. John’s deterioration quickened.

“He was released too soon after that from conservatorship,” Steve Maurer said, faulting an adversarial court process that too narrowly frames conservatorship as a form of incarceration.

“God bless them, those public defenders, they do good things,” he said. “But their goal in life is to win their cases, get everybody off conservatorship because that’s a terrible thing to be on. It’s completely broken. I think they should say if you’ve been hospitalized X number of times or have medical problems as a result of grave disability, the bar is going to be much higher to have you released from conservatorship.”

Three months after his release, in May of 2016, John was arrested for public drinking in Downey.

About a year later, another sister, MaryRose, found John outside a Starbucks in Hastings Ranch and flagged down a police officer who helped talk John into going with him to Las Encinas Hospital, a sprawling psychiatric care campus in Pasadena.

John had been there before and checked out without any family members being notified. This time Dusseault waited 72 hours — the maximum involuntary hold unless the hospital accepts him as a long-term patient — and stood out front with a peer counselor from a nonprofit agency who accompanied her as a friend.

“We had a whole plan of housing,” Dusseault said. “I was going to pay for it. We were all set to go.”

She had found a vacancy in a board and care home. Generally in rambling houses or converted apartment buildings where residents share bedrooms, these homes are the backbone of long-term care for those whose mental illness is stabilized.

They provide 24-hour supervision and care that includes meals, housekeeping and managing residents’ medication. But an antiquated, and inadequate, reimbursement scheme based on disability income is forcing many to close. The Los Angeles County Department of Mental Health reported in July of 2020 that 51 board and care homes had closed over the previous four years, eliminating 1,338 beds.

With openings hard to come by, Dusseault found a bed in one of the unknown number of unlicensed homes that provide whatever services they believe their residents need and charge what the market will bear. John had once thrived in an unlicensed board and care, until the owners walked away, leaving their residents to be evicted.

Dusseault was willing to give it another try. John wasn’t. As she waited in front, he ran out the back.

He had been released without a plan. She had seen it so many times before.

“Sometimes he’s released with a discharge paper saying he should take medication,” she said. “Sometimes with a bottle of medication, sometimes nothing.”

b

There’s no accounting for the cost in dollars of John’s untreated mental illness. Based on Medicare’s reimbursement rate for acute psychiatric hospitalization, a stay at Las Encinas would come at a cost of more than $1,000 a day in today’s dollars. A county study earlier this year reported that the county spends about $654 a day on high-need inmates like John in the mental ward of L.A. County Jail. The more than 400 days he has spent there over the last 26 months have thus come to more than $250,000, enough for almost four years in community-based treatment that, unlike jail, can be reimbursed by Medicare.

Including emergency room charges, paramedics and court costs, the total over the decades would amount to well more than a million dollars.

Because of his multiple disabilities, John would have priority for permanent supportive housing, a subsidized apartment of his own with a case manager checking in on him occasionally.

That might have worked in John’s youth, when it was still reasonable for him to imagine a normal life. But at this point, he was far too ill to live on his own.

Looking back over the years, Dusseault finds that John has done best in board and care homes. After another 72-hour hold, Dusseault persuaded a doctor to release John to Sunshine Assisted Living, a 68-bed licensed board and care home in Lynwood. It worked out well for nine months, one of his longest stable periods. But with reimbursement fixed at about $35 a day, even licensed homes have no means to provide the support required by John’s complex psychiatric disorder. Eventually he began walking around the neighborhood and got into conflicts with neighbors. One day he didn’t come back.

Sometime in 2018, a text came from Dusseault’s nephew, a paramedic.

He had been called to a restaurant where John was in distress. She rushed there to find him disoriented, emaciated, limping and covered in feces.

“I beg him to get him into my car,” she said.

He refused, and the firefighters did not think he met the standard of gravely disabled required to take him on a 72-hour hold.

“They have to let him go,” she said. “I follow him. He dives into this back alley. I lose track of him.”

From the inmate locator, she learned that he was arrested the next day.

A flurry of arrests followed, in March for discharge of a noxious substance — most likely feces, his sister said — and April for trespass. His May arrest for indecent exposure put him on the sex offender register and led to a hearing on his competency. In November, after spending 11 months on and off in jail, he was found competent to stand trial and released for time served.

The following January he was arrested for disorderly conduct and public drinking and in February for battery. Another competency hearing followed. A judge again found him competent to stand trial in May.

In November of 2019, he was arrested in Torrance, again for indecent exposure.

With his sister pushing in the background, John was sent back to the mental health court for a competency hearing. On Dec. 14, the judge found him mentally incompetent to stand trial and ordered him to a state hospital for treatment.

Since John’s earlier treatment at Metropolitan State Hospital, a shortage of mental beds had overwhelmed the state hospital system. In November 2019, more than 800 defendants judged incompetent to stand trial were waiting to get into a state hospital. John never made it to the top of the waitlist.

Often strapped into a bulky quilted vest and chained to a metal table during visits with his sister, John languished for 200 days in L.A. County Jail, a common fate of hundreds of defendants judged incompetent to stand trial, who often wait in jail far longer than the statutory terms for their crimes.

Using the online purchasing system, Dusseault made sure he had basic toiletries.

In February of 2020, John was ruled to have regained his competence to stand trial. By then John’s public defender and the deputy district attorney were willing to try something new — diversion.

Under a court order suspending his trial, John was placed in a group home in South Los Angeles operated by the county Office of Diversion and Reentry, where he would be under psychiatric supervision.

There, a good start again turned bad. This time the catalyst may have been a $25,000 check John received for back disability pay, the third time he had received such a lump-sum payment.

During jail stays, those benefits are suspended, then paid in arrears when the recipient requalifies.

The community-based model followed by the diversion program seeks to support as normal a life as possible, allowing residents to come and go as if living independently. The money soon found its way to the street. John resumed using meth.

Eventually he had an altercation, was arrested and transferred to a locked facility.

Dusseault does not know how long he remained there before he went AWOL. He was next spotted in mid-June at the Pasadena strip mall.

After he deflected her offer of shelter, it was only a few days before she saw John’s arrest pop up on the inmate locator.

At his next court appearance in August, Dusseault waited in a courtroom in the Airport Courthouse for a ruling. Would John be sent to prison or given one more chance? She had spoken to his new public defender and was hopeful that she would push for a conservatorship.

Led into the courtroom with his hands tied to his waist in shackles, John saw his sister and broke into a childlike smile, twisting his wrist to wave his hand.

Her face broke into a smile when Judge William L. Sadler ordered a psychiatric evaluation. That meant John was on the conservator track. And it would be different this time. She would apply to be named his conservator. She would try to find him a placement near her home in Pasadena, where she could monitor his care and know immediately if he goes off course.

In October, Dusseault returned to court and, at last, became her brother’s conservator.

Imperfect as conservatorship proved in the past, she believes it’s the best that could have happened at this stage, especially since, this time, she will be engaged in his care.

But five weeks later, John remains in jail. His release awaits Dusseault’s finding a residential psychiatric facility. So far, she has found them to be either full or unwilling to accept a new patient with John’s problematic background. After striking out in Los Angeles County, she’s looking into one in San Bernardino County that would be near their brother Steve.

For Steve, John’s best hope faded long ago, when California discarded institutions like the one in Washington state where his schizophrenic great-uncle Leonard lived for most of his adult life — before the invention of psychotropic drugs.

“You could argue he had somewhat of a life,” Steve said. “He lived into his 80s. He was protected. Nowadays, no one is committed like that unless they commit a crime. They end up with their lifetime greatly reduced.”