It’s not all fun and games

While visitors relax, Magic Johnson Park does crucial work, capturing and recycling water

Translation: It’s not only going to be a dry year, we may be in the middle of a decades-long “megadrought.” In Northern California, sobering aerial photos show Lake Oroville at 42% of its capacity.

Subtext: We need to be smarter about capturing the rain we do get, much of which is flushed out to sea in chutes of concrete.

It’s really a story of design — about the ways water is designed to travel along the surfaces of our city, and how we can tweak those surfaces so that we

But L.A. is finding other ways to capture and to store water. And in some cases, it is run-of-the-mill urban infrastructure that plays the starring role. Your neighborhood park? It might just be doing double duty as critical aquifer.

Strategic landscape design and water engineering is transforming neighborhood recreational areas into sites where water is captured, cleaned and stored. That water is then recycled and used to irrigate park vegetation; excess water can be released back into the river system in far cleaner form. All of this is being designed in ways that are barely visible — if visible at all.

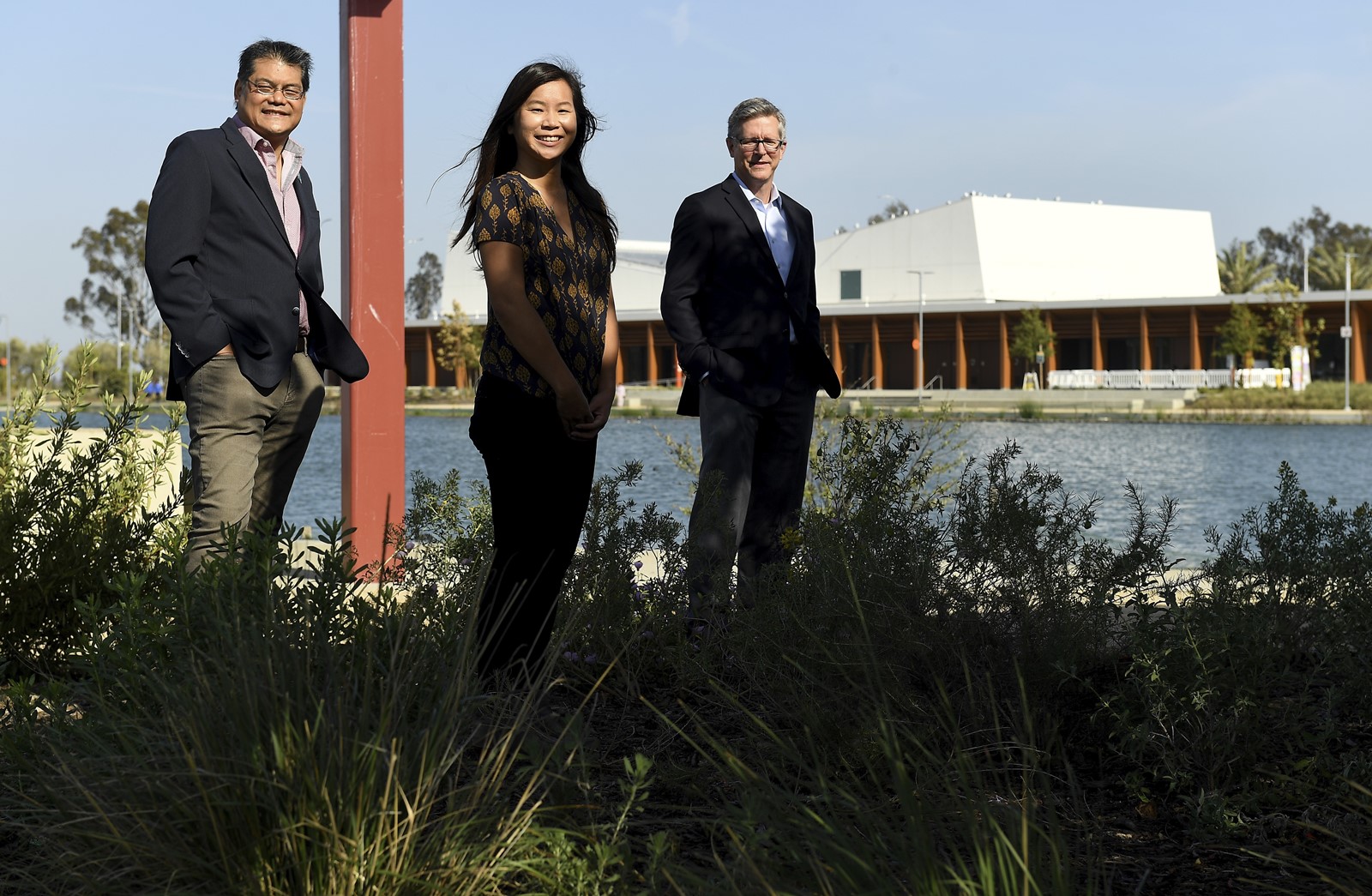

“It’s taking infrastructure but making it an asset to the community,” says landscape architect Gary Lai, a principal at planning and design firm AHBE/MIG. “You can do the water conservation part and it would be good. But then putting in an amenity for a neighborhood that didn’t have it, that’s fantastic.”

Parks around Los Angeles have water storage systems tucked under ballfields and recreation centers. In Santa Monica, there’s a 200,000-gallon cistern beneath a public library. And at Magic Johnson Park in Willowbrook, an unincorporated community in South L.A., Lai and an AHBE/MIG team helped develop the design for an ongoing $83-million renovation.

It’s a location with a fraught history. Magic Johnson Park lies on the site of an oil storage facility, the former Athens Tank Farm operated by Exxon Mobile until 1963. In the 1970s, a piece of the property was used in a real estate project called Ujima Village, backed by the Department of Housing and Urban Development. Intended to help working-class Black families find a path to homeownership, the development housed 600 people in one- to four-bedroom units that shared a playground, basketball courts and a community garden.

But by the 1990s, Ujima Village fell into disrepair and ownership went to L.A. County. Tests at the time showed the land remained contaminated from previous oil operations. In 2008, the California Regional Water Quality Control Board ordered Exxon Mobile and L.A. County to clean up the site. Residents were relocated and the development was razed.

After years of environmental remediation, the water quality board and Department of Toxic Substances Control allowed the land to be used as a park (Exxon continues to monitor it for methane and other contaminants). Visit the park today and you’ll notice pleasing surface changes. There are new jogging paths, drought-tolerant native-plant gardens studded with sagebrush and sycamores, scenic overlooks and a handsome community center designed by Paul Murdoch Architects with shimmering interior murals by L.A.-based artist Carla Jay Harris. The park’s two lakes, previously clogged with algae and sediment, are now a clear blue.

Largely out of sight are landscape design and engineering moves that have transformed the way the park uses water. Prior to the renovation, the 126-acre Magic Johnson Park used potable water to irrigate its gardens and grass lawns.

“If you think about what we do, it makes no sense,” says Dan Lafferty, water resources deputy director at L.A. County’s Department of Public Works. “We import water from the Colorado River and then we dump it on the ground.”

They achieved this in five steps: Divert, clean, employ nature, irrigate and capture.

Rainwater, along with water used on lawns and to wash cars, ends up in storm drains, which flush water to the L.A. River and ultimately to sea. So the team turned to the 84-inch drainpipe under El Segundo Boulevard, at the southern edge of Magic Johnson Park. That pipe captures nearby runoff and deposits it into Compton Creek.

But engineers diverted the water and fed it into a small pumping station where garbage could be removed. From the pumping station, the water is piped to a small water treatment plant near the park’s community center, where it is treated with alum and ozone to kill any bacteria.

The shrinking of water-cleansing technology in recent decades is part of what makes a water recycling project within a city park feasible, says Lai. “In the 1960s, this would have been the size of a city block.”

The treated water is slowly released into newly planted wetlands near the park’s southern lake. Here, the water receives another level of cleaning as it filters through saltgrass, native sedges and Arroyo willow, as well as a porous stone barrier. “Whatever didn’t get treated by the alum and ozone,” says Lai, “is dealt with by the plants.”

The wetlands and new native gardens create a critical ecology for native and migratory bird and butterfly species, one that’s also pleasing to humans. “It’s rethinking what a lake is,” says AHBE/MIG landscape architect Wendy Chan. “You get to see these native plants, you see the blooming cycle, you see all of these species.”

Once the water is sufficiently cleaned, it can irrigate the park or be released back into Compton Creek. End result: The park is watered without having to open a tap, and the filtration process helps mitigate coastal pollution.

With two lakes, the park is also an important water storage site. The system was designed to handle the cleaning and filtration of water during heavy rainstorms, and each lake can accommodate up to a 1-foot water-level rise.

After storms, that water can be stored for future use or slowly released into Compton Creek as necessary. “It acts like a treatment facility,” Lai says.

Magic Johnson Park reflects a new way of thinking about how existing land can be used for infrastructural purposes, such as water storage.

“Our largest spreading ground is 450 acres by Pico Rivera,” says Lafferty, referring to the Rio Hondo Coastal Spreading Grounds, a water storage facility. “But we don’t have a 450-acre parcel for me to gather water. So now you’re talking about multiple smaller projects.”

Those smaller projects could be L.A.’s public parks, which cumulatively add up to thousands of acres of land.

In addition to Magic Johnson, the Department of Public Works is devising a similar concept at the Rory Shaw Wetlands in Sun Valley. In Silver Lake, designers leading the ongoing master plan process for parks surrounding the reservoir are looking at drought-tolerant landscaping, the introduction of wetland ecologies and a stormwater capture system to keep the reservoir replenished.

Other parks achieve a similar mission on a smaller scale. Westside Neighborhood Park in West Adams draws runoff for irrigation. Echo Park Lake, which once employed potable water to maintain the lake, now recycles and cleans area runoff for that purpose.

The projects were funded, in part, by recent bond measures, such as Measure W in L.A. County and Proposition O within the city of Los Angeles, which were designed to improve the quality of stormwater runoff. In the process, they have helped improve the design and resiliency of parks themselves.

Projects such as the one at Magic Johnson Park — with its intensive water engineering components — are part of a shift in focus in landscape architecture.

“The field of landscape architecture has been going through a transition these last 10 years, especially with sustainability,” says Lai. “We were a profession that dealt mostly with the aesthetic. Frederick Law Olmsted built Central Park mainly for aesthetics — though there were health and welfare aspects. Now we are thinking of aesthetics and melding it with hard science and ecology.”

Landscape architecture is often treated as an afterthought — a way to gussy up the place after a building is done. But climate change and shifting attitudes toward the environment have made the field ever more critical. And, in Los Angeles, a city with little green space and even less water, it couldn’t be more essential to create water-conscious public spaces that are also joyful and aesthetically pleasing.

“Los Angeles imports about two-thirds of its water,” says Lafferty. “We get a third from the Colorado River and a third from Northern California and a third locally. And that means we are in drought all of the time. So you have to plan for that. You have to grow that local source.”

Smartly designed parks are helping us do that.