A crisis on top of a crisis

South L.A.’s MLK hospital serves a community already hit hard by health inequities even before the COVID pandemic

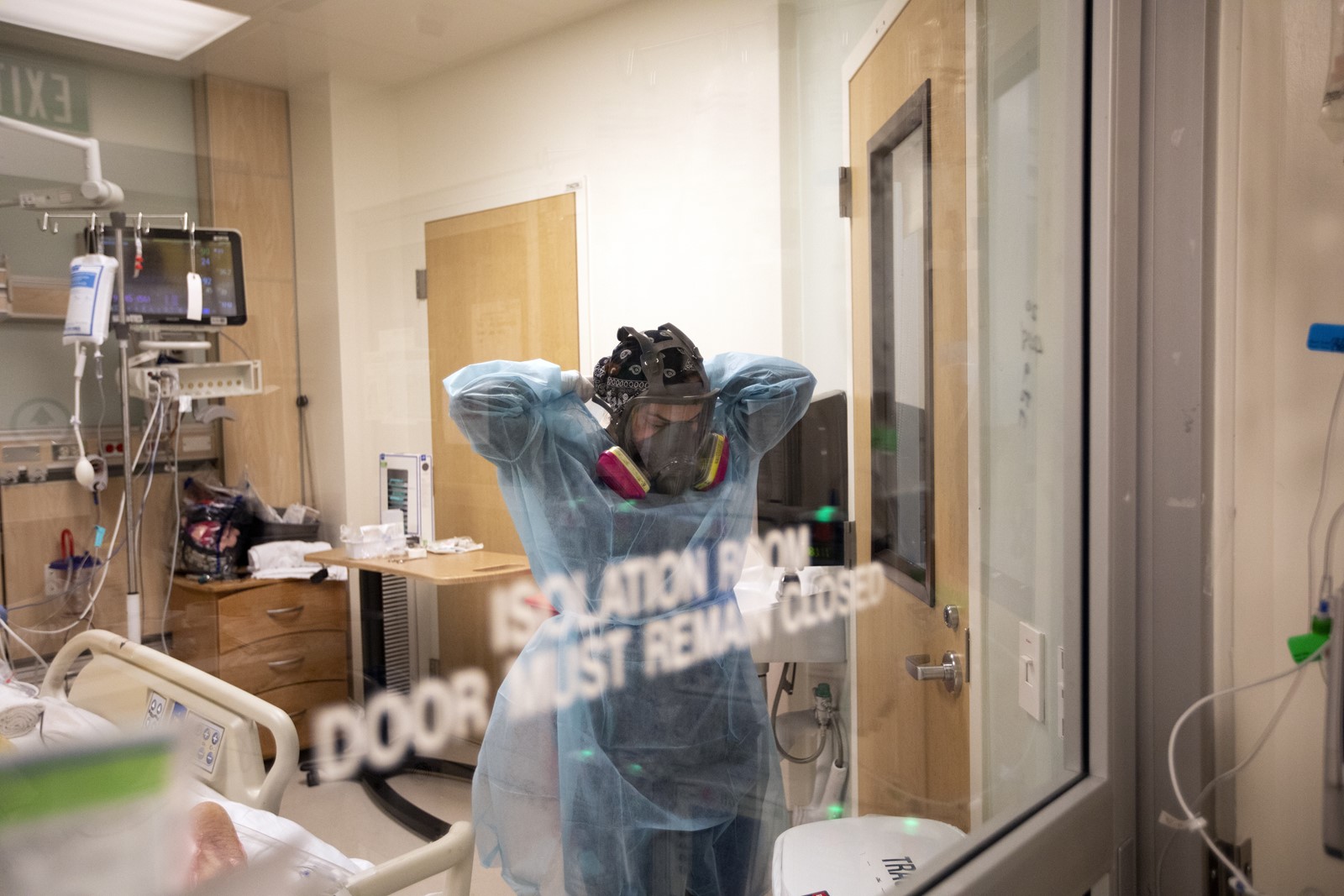

Under the hum of mechanical equipment and the steady chirp of a heart-rate monitor, a COVID-19 patient lies quietly in the intensive care unit of Martin Luther King Jr. Community Hospital.

She is 65, clad in the same bright yellow gown as the other nine patients in the unit, and her eyes are closed as a mechanical ventilator pumps air into her body behind sliding glass doors.

A nurse comes over and whispers that the patient’s husband is on his way to the hospital, but the announcement is not one of relief: He’s coming in an ambulance. He’s sick, too.

It’s a story that is playing out over and over again in South Los Angeles, where poverty, density and the inequities of the American healthcare system are crashing headfirst into a worsening pandemic, contributing to an already sick community that’s getting even sicker. The population served by Martin Luther King Jr. hospital is largely Latino and Black, both communities that have been hit hard by the pandemic. Many residents live in dense, multigenerational housing, work essential jobs and suffer from secondary health conditions due to a lifelong, systemic lack of access to quality primary care.

Hospital officials said the combination of factors was, in many ways, a recipe for disaster.

“This community was sick ahead of time,” senior communications director Gwendolyn Driscoll said as she rode an elevator to the fourth floor of the hospital, which is being converted into additional space for intensive care units. “We were already, basically, a combat-zone hospital before COVID.”

Yet the gleaming, state-of-the-art building shines like a beacon in Willowbrook, an unincorporated area between Compton and Watts. Erected in 2015, the hospital was built in place of — and many hoped over the memory of — the disastrous Martin Luther King Jr./Drew Medical Center, which was closed in 2007 following a Times investigation into dangerous conditions.

The new hospital was designed with 131 beds and 20 ICU units, but the pandemic has far overtaken those numbers. On Thursday, it had 225 patients, 135 of whom had COVID-19.

In response to the surge, most single-person rooms at MLK now hold at least two patients. Field hospitals and medical tents have been erected outside to assist with intake and triage. A meditation space on the ground floor — replete with stained-glass inlays and soothing stone walls — now holds 10 cots awaiting the next to arrive. Like several other hospitals in Los Angeles County, MLK declared an internal disaster this week, which allowed it to divert ambulances for a few hours from its besieged emergency room.

But MLK is juggling a higher rate of COVID-19 patients than any other hospital within a 15-mile radius, officials said, making it one of the hardest-hit hospitals in one of the hardest-hit regions in the world.

The COVID-19 testing site in Willowbrook has a 32% positivity rate — nearly twice the county average, according to the hospital’s analysis.

“We are dismayed by the disproportionate impact that COVID is having on our community, but we are not surprised by it,” Dr. Elaine Batchlor, MLK’s chief executive officer, said Tuesday. “Even before COVID, we were dealing with a difficult situation. We were dealing with an epidemic of poorly treated chronic illness.”

According to the L.A. County Department of Public Health, South L.A. ranks lower than the rest of the county on several key health indicators such as obesity and nutrition, and its residents are significantly more prone to worse health outcomes such as diabetes, cancer, cardiovascular disease, stroke and high blood pressure. More than 30% of households in the area reported food insecurity, while 32% of adults reported difficulty accessing medical care — more than any other area in the county.

Before COVID-19, the area had a mortality rate 22% higher than the county average, the hospital said.

Batchlor said diabetic amputations, sepsis treatment and dialysis are among the most common procedures at the hospital, all of which are complications that can be prevented with good disease management and quality outpatient care.

Yet the community has the fewest hospital beds per person in the county, she said, and the hospital has more COVID-19 patients than some that are three or four times its size.

“I describe our healthcare system as separate and unequal,” Batchlor said, “and we have a community here that is a reflection of that. We’re all Black and brown, low income, almost all publicly insured, and really lack the access to healthcare that other communities have. Because of that, we are being hit hard — harder than every other community — by COVID.”

In addition, many patients are essential workers who are continually exposed in the community — they are “the people stocking the grocery stores, driving the buses and cleaning up after the rest of us,” Batchlor said — who live in housing that doesn’t easily allow for isolation.

“All of those social conditions combined to create what I call a classic public health crisis,” Batchlor said.

Yet MLK appears to be managing the surge, as evidenced by its quiet hallways and orderly system of intake. It’s something Driscoll attributed to years of practice handling trauma: Even before COVID-19, the hospital was treating 110,000 patients each year in an emergency department built for 40,000.

“This is a team that has spent a lot of time thinking about efficiency,” Driscoll said.

On Tuesday, that practice and preparation were apparent. Patients were moving through the intake and triage tents quickly, and the hospital was surprisingly quiet — perhaps because in most cases, visitors are still not allowed. Three ambulances were parked outside the receiving area, but all had been offloaded upon arrival.

The two beds inside a former gift shop space that was converted into an overflow area sat empty, although Driscoll said both beds had been used by patients several times within the last week.

Despite the seasoned air of control, officials said the worsening surge is alarming, and the hospital does have limits.

“We are not operating in a normal situation now,” Batchlor said. “We are stretched thin, we are strained. The fact that we have been able to adapt and continue caring for patients is a positive thing ... but the situation is not good.”

The hospital has asked state and county officials for help addressing some of its COVID-19-related challenges, including the need for more nurses, doctors and respiratory therapists. South L.A. has one-tenth the number of doctors as more affluent areas of the county, according to hospital data.

On Dec. 26, a team from state and county health departments and EMS agencies toured the hospital to determine how to assist, Batchlor said. One of the larger, more systemic issues she hopes they will address is the need for a mandatory system to help redistribute patients among Los Angeles hospitals more evenly.

It’s an issue tied largely to health insurance.

“Most hospitals lose money on publicly insured patients, and they try to make up for that by maximizing the number of commercially insured patients they have,” Batchlor said. “And since almost all of our patients are publicly insured, our patients are not the kind of patients that other hospitals are eager to have.”

Currently, more than 90% of the patients at MLK are under- or uninsured. Only 4% have commercial insurance, and they are far easier to transfer, Driscoll said, adding, “This is what structural inequality looks like in the middle of a pandemic.”

The hospital also has a high prevalence of patients with addiction and behavioral health issues, Driscoll said, so much so that a separate tent had to be erected outside just to assist those people as they are admitted.

Until more help arrives, the hospital and its workers are managing the pandemic “one hour at a time, one day at a time,” said Chief Operating Officer Jeff Stout.

“As an operator, I think about [the worst-case scenario] every day, but I still don’t know the answer to the question,” Stout said. “You just have to break it down into smaller increments and work your way through each individual situation and each individual patient.”

The approach seemed to be working for Mojisola “Lucky” Peregrino, a registered nurse in one of the outdoor field tents Tuesday.

All 15 stations inside the makeshift tent were occupied by patients who were being assessed for COVID-19 intake. Some were on their phones while others curled up under a blanket, with bare utility bulbs buzzing overhead.

Peregrino said many patients are frightened or panicked when they arrive, particularly those who are having COVID-19-related respiratory issues, so she focuses on calming them down, lowering their heart rates and reassuring them that they’re in good hands.

“I’m a nurse, so right now I worry about the patients I have to take care of,” she said. “We have to support each other, be gentle with each other and be kind to each other.”

It’s an ethos displayed by many of the healthcare workers at MLK, who, despite conditions that might easily overwhelm, said they are drawn to the hospital specifically because of its mission to serve its community — a community that was all but forgotten by the nation’s healthcare system long before the current crisis began.

In the ICU, Dr. Jason Prasso said he has worked to develop a post-care system for those who recover from the coronavirus, including regular check-ins to help maintain their health.

Prasso said patients who can return to homes without food insecurity or financial issues are in a much different situation than many of the patients he treats.

Some without health insurance can’t afford physical therapy, while others may soon face eviction because they couldn’t work while they were in the hospital. Others still can’t turn to their families for in-home care because they have to continue to work amid the pandemic.

“It just snowballs,” he said while wearing a thick, air-purifying helmet. “We’re trying to be as comprehensive as we can be, but it’s even a challenge for some people to get to appointments.”

As he spoke, he continually scanned the 10-bed ICU for any signs of emergency. Behind him, lights blinked, nurses checked vitals and patients’ chests heaved and deflated with mechanical regularity under thin green blankets.

Prasso holds onto hope for all of his patients, he said, but the statistics suggest that 7 out of 10 COVID-19 patients on a mechanical ventilator won’t survive.

Just hours later, the patient whose husband was en route in an ambulance succumbed to the virus, he said Wednesday.

Now Prasso and the rest of the healthcare workers at MLK are bracing for the post-Christmas surge of COVID-19 that is expected to arrive in the coming weeks.

They’re as ready as they can be, but for a hospital already struggling under the weight of one healthcare crisis, he knows the odds aren’t always on their side.

“The patients here,” he said, “are particularly helpless in this battle.”