He likes what he sees in the Senate’s climate deal

Jerry Brown is pleased that Sen. Joe Manchin climbed on board.

When news broke late last month that Sen. Joe Manchin III had agreed to support a sweeping climate bill — and that it would include $369 billion to support clean energy and environmental justice initiatives but would also require continued oil and gas leasing on public lands and waters — it was hard not to wonder: What would Jerry Brown think?

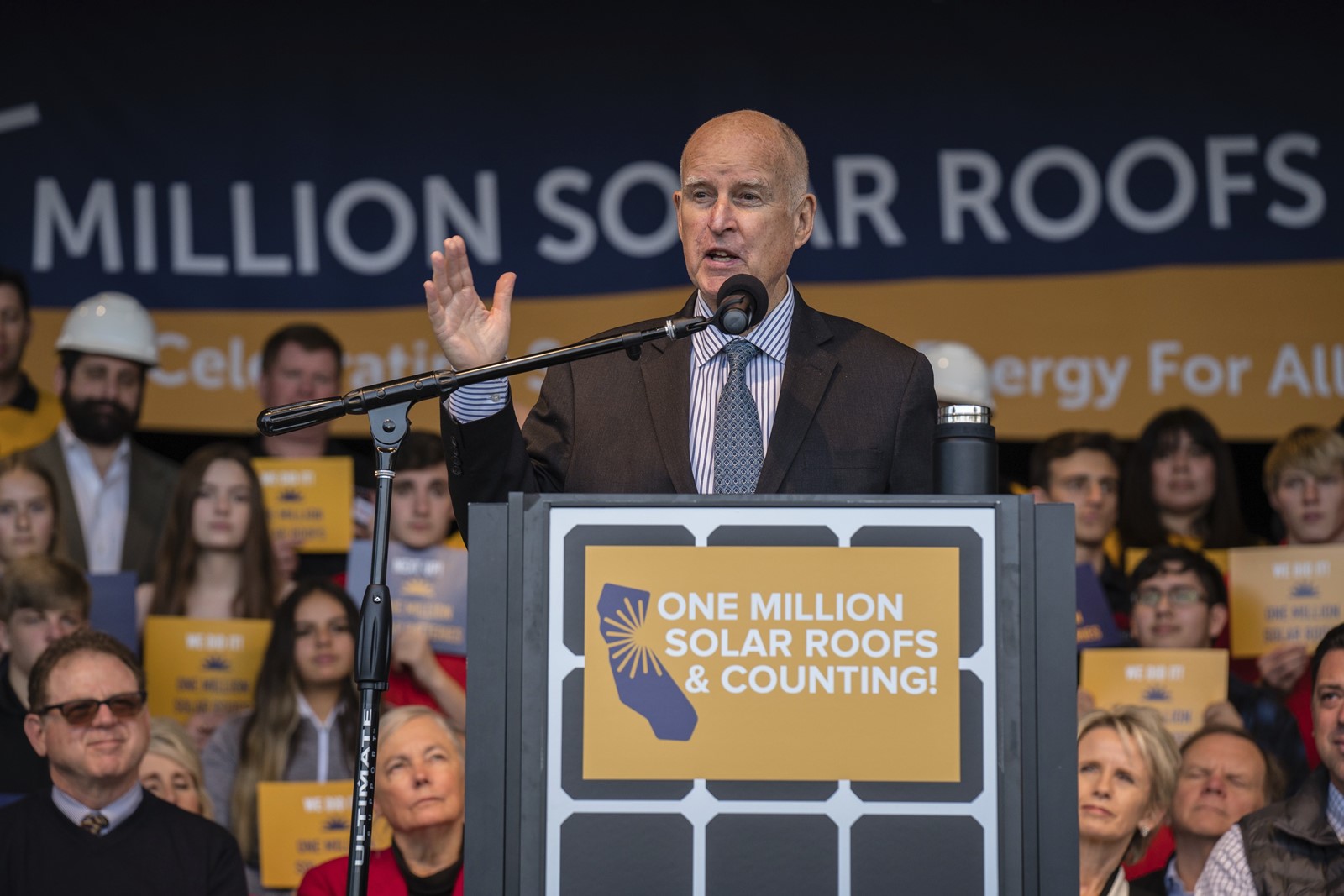

Brown is considered a global leader in the climate fight. As California governor, he signed a 100% clean energy law and served as an unofficial climate ambassador abroad. He faced criticism for doing little to limit Golden State oil production, but he was still miles ahead of most high-profile politicians.

He’s continued working on climate since leaving office in 2019, chairing the California-China Climate Institute and serving as executive chair of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists.

So what did Brown think about the politics of the Manchin deal, and the trade-offs made to win over the coal-loving West Virginia Democrat — including a plan to speed up the approval process for natural gas pipelines and other fossil fuel infrastructure?

The former governor spoke last week with The Times from his Colusa County ranch, where he said it was 102 degrees outside. Fortunately, the climate-friendly electric heat pump he’d installed at his off-the-grid, solar-powered home was keeping him cool.

“It heats and cools. So far it’s been very good,” he said.

Here are some highlights from the conversation, edited and condensed for clarity.

I was surprised. I was not informed of the internal machinations of the Senate chamber. So things may have been going on all the time. That’s probably why President Biden kept pushing, because there were indications that Manchin would eventually vote for something. As I’ve learned, the legislative process — you don’t always know what people want. Very often, the legislators don’t know what they want.

And this is all very new. During the Trump time, when there was Republican control, they didn’t want to do anything on climate. There’s still a massive idiosyncratic climate denial by Republicans in the American Senate. So it has just been the Democrats working on this thing, and they haven’t really had a lot of habit. As a Congress, they should have been working on this stuff since they first heard about it from James Hansen back in the ’80s.

It’s a huge bill. That’s a lot of money. People are saying it’s the most significant move on climate ever.

Now is it bigger than Build Back Better? Well, that was an idea, that was a proposal — that was the president’s imagination. Now we’re dealing with something that is getting close to being real. That’s the way the process works. You have to go from idea to realization, and there’s a lot of modification along the way.

So I would say this is very impressive, and it’s a good sign that Manchin decided to go along. Because it means that he appreciates what’s being done, and he wants to be part of it. That’s a validation of concept for climate action. It’s getting traction.

Like sausage, you don’t want to look too closely at how it’s made. When I got the gas tax bill in California, to get the one Republican vote that I got in the state Senate — that senator got $500 million in transportation programs for his district. That is the nature of the legislative process.

We’re locking in emissions right now. We have coal plants, gas plants. How many vehicles do we have on the road, and how long are they going to last? If you want to get serious, you could say, “OK, in two years we’ll take away all the gas cars, we’ll buy them from you. And you’ll get an electric car in return.” That’s not feasible. We’re still a fossil fuel civilization.

Now, we’re moving away. In California, we get half of our electrical generation from renewables, if you count nuclear and hydro. But if you want to win victories, you’re going to have some more oil leases. We are drilling new oil wells every day. If you want to reduce the oil produced, you must reduce the oil consumed. It’s just that simple. If you don’t reduce consumption, and you reduce production in America, they’ll just get that oil from somewhere else.

So the goal is to reduce consumption. This bill does that, and it does that with all these different investments. So it’s not perfect, but we don’t live in a perfect world. There are 50 Republicans in the Senate, and they don’t want to do any of this.

This is good what we’re doing — but no, it’s not enough. Even California is not doing enough. The country and state are doing all they can politically, and they’ll do more. But the resistance is huge. You can get $40 billion for Ukraine from Congress. It’s pretty hard to get $40 billion to change out the automobile fleet from fossil fuel to renewable.

You have to have a clear view here. This is Mitch McConnell’s Congress as much as it is Chuck Schumer’s.

I’ve been trying my darndest to get a closer partnership with China. China is 27% of global emissions, America is 13%. So China and the U.S. must be the leaders. That is the most important form of leadership, a joint effort by China and the U.S. to move as rapidly as possible to a zero-emission economy. It’s going to take decades, but we’ve got to get going.

If you want to get more gas-fired plants, the best thing to do is to shut them all down now. And then when the massive blackouts come, the politics will be so powerful that you’ll get even more gas plants than if you make sure that the lights don’t go out in the meantime.

If you push too far, there’s a backlash. When my father was governor, he had a water plan, a master plan of education, civil rights. And then Reagan comes in, wins by a million votes. Then I’m in office eight years, and I appoint some pretty liberal judges. Then Deukmejian comes along, and then Pete Wilson comes in. He appoints very conservative judges, builds 20 new prisons.

So if you maybe try to move slower, you end up moving faster. What is that about the tortoise and the hare? The idea is to achieve the goal. And what is the fastest way to do that? Doing it in a manner that continues uninterrupted. And to do that, you have to avoid backlash.

Supporting domestic production of battery technology, of solar panels. What did the Chinese do? They brought the cost down. They went from very little to 80% of the world’s solar manufacturing, and they did it with government investment. So they’ve shown the way. A close collaboration between public investment and private business can achieve a lot. And I think building up our own domestic industry will make it more popular, will build a constituency that will then promote it even more.

Getting more gas cars off the road is also good. The provisions are myriad, and they all fit into a piece. It’s not one thing. Emissions are coming from gas wells and belching cows, and we’re burning up oil. Plastics. You’ve got ships, you’ve got planes, you’ve got trains, you’ve got houses. There are so many different sources of this that we must bring down much faster.

You’ve got to have electric heating, and you’ve got to have electricity generated by renewable energy, or storage. There’s so much to do that in the short term, you’ve got to throw a lot of money out. Of course you want to do it wisely.

We have a lot of other sidebar activities that seem very important — but they’re not as important as climate change. It’s the No. 1 existential threat, and even if we accelerate our moves, there’s going to be massive migration. There’s going to be political instability. The biggest human rights issue, bar none, is a billion people in India and other parts of the world that are going to suffer because they don’t have nice air conditioning like most Americans have. They’re going to suffer greatly.

I think even Gavin Newsom wants to keep Diablo Canyon open. It is a fair argument. Certainly keeping some nuclear plants open, that’s an easier question than building new ones, because the current technology takes an awful long time, it’s very expensive. Certainly investing in a safer, more standardized, more modular nuclear is a good idea.

With existing plants, you have to look at each case, look at the merits. See what your alternatives are. For example, Germany closing down nuclear and buying coal — no, I don’t agree with that. They should have kept them open for a while.

I’m not going to weigh in on that one. There are a lot of people who have their views. I know some people who think it should not stay open. Other friends of mine, equally intelligent, say, “No, keep it open for a while.”