A Breyer retirement could help the court

Stepping down might lower the temperature

The agitation understandably increased after some maddening comments by the Senate minority leader, Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.), on Monday. McConnell suggested that if Republicans took back the Senate, it would be “highly unlikely” that the Senate would confirm a Biden nominee if a vacancy arose in 2024.

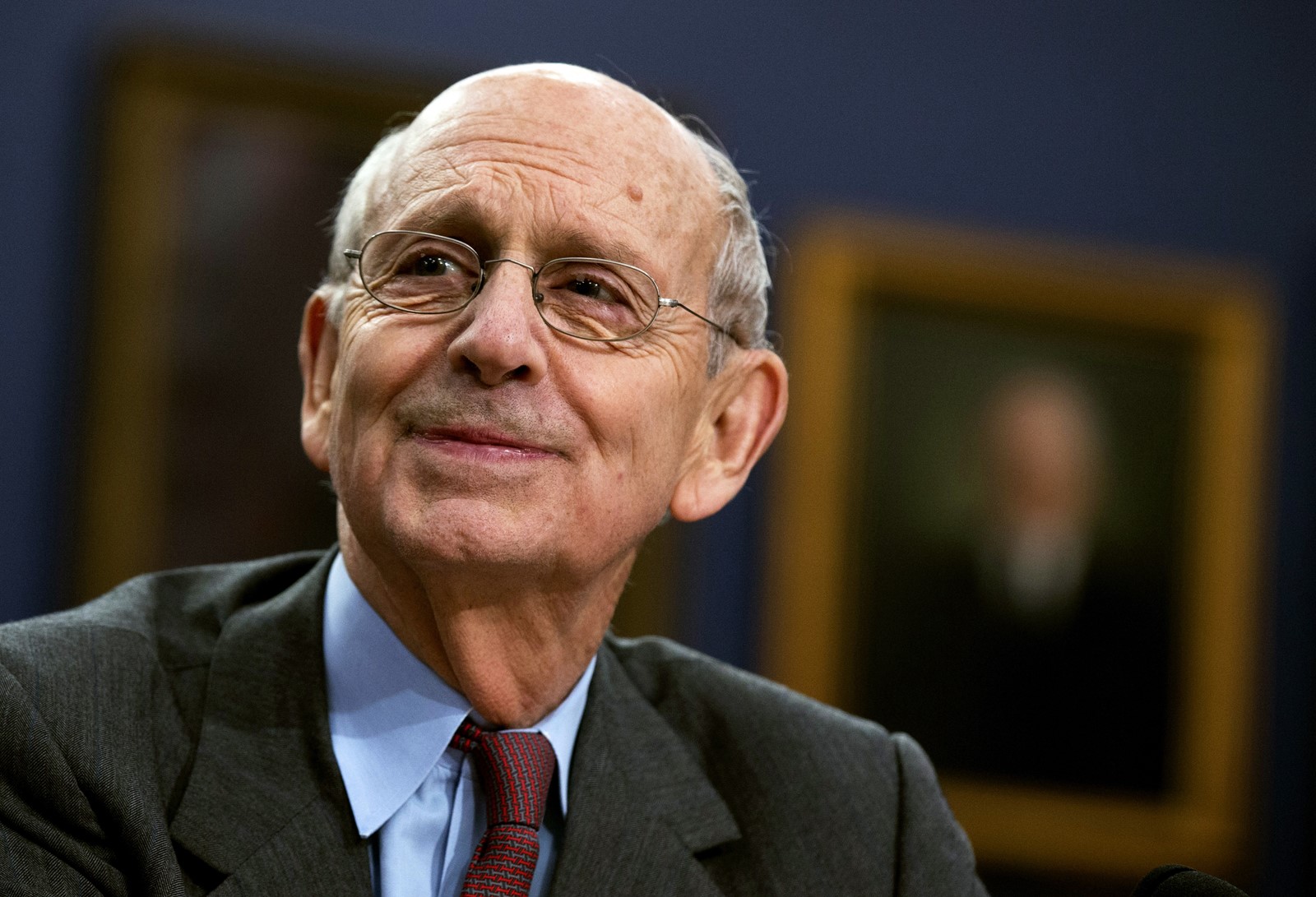

Breyer’s refusal so far to say he will retire this year isn’t surprising. In a virtual lecture at Harvard Law School in April, the 82-year-old Clinton appointee and San Francisco native made it clear that he was unlikely to be moved by calls for partisan solidarity. Breyer said that his experience as an appellate judge showed him that when judges take their oath “it is not to the political party the helped to secure their appointment.”

But Breyer should consider a different and somewhat paradoxical argument for stepping down: that his remaining on the bench under current political circumstances will make it harder for the court to reclaim a reputation for standing above partisan politics.

The court’s image as a nonpartisan institution has been undermined by two related developments: an ever-more-partisan Senate confirmation process and a growing perception that in important cases justices vote not only along ideological lines but also, increasingly, along partisan ones.

Both parties in the Senate have blocked or opposed qualified judicial nominees proposed by presidents of the opposite party. But in 2016 McConnell, then the majority leader, took partisan obstruction to a new and outrageous level with his refusal to consider President Obama’s nomination of Merrick Garland to succeed the late Justice Antonin Scalia.

McConnell justified his stonewalling by arguing that the Senate shouldn’t confirm a Supreme Court nominee in a presidential election year because the American people “should have a voice in the selection of their next Supreme Court justice.” McConnell went on to shamelessly violate that purported principle in 2020 when the Republican-controlled Senate rushed to confirm President Trump’s election-year nomination of Judge Amy Coney Barrett.

McConnell argued that the Barrett confirmation was appropriate because the Senate and the White House were controlled by the same party, a rationalization that also lies behind his suggestion this week that a Republican Senate wouldn’t confirm a Biden nominee in 2024. (McConnell wasn’t clear about whether a Republican Senate would act on a Biden nominee if a vacancy opened at the end of 2023.)

Breyer and Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. are right that Supreme Court justices aren’t politicians, and it’s notable that the justices don’t always align according to the party of the presidents who appointed them even in some politically charged cases.

Yet it’s also true that the party of the president appointing a justice will often predict how that appointee will approach the law and the Constitution. That’s partly because presidents of both parties in choosing Supreme Court nominees are increasingly considering judicial philosophy as well as legal credentials, tightening the connection between party and ideology. And both parties have made the future of the Supreme Court a campaign issue, especially in relation to abortion.

Against that background, it’s not surprising that the selection of justices has been poisoned by partisanship, especially when the death or retirement of a justice seems to portend a shift in the court’s direction.

When Scalia died, Republicans were determined that Obama not be permitted to appoint three justices over his two terms. (Never mind that Ronald Reagan named four justices over his presidency.) Democrats were appalled at the possibility that the death of Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg would allow Trump to name a third justice in a single term — and Senate Republicans added insult to injury by bestowing on Barrett the election-year approval that Garland was denied.

This editorial page has supported a fixed nonrenewable 18-year term for Supreme Court justices which in some versions would guarantee that every president would appoint two justices in a single four-year term. Those reforms would lower the political stakes of any individual appointment, and fixed terms also would make it likelier that presidents would consider older and more experienced judges and lawyers when a vacancy arose. (The size of the court would change while the reform was being implemented but would eventually revert to nine.)

We acknowledge that this sensible reform is a long shot, so meanwhile it’s important to try to lower the political temperature in other ways.

That brings us back to the decision facing Breyer. He is thought to be reluctant to step down because it would seem like a partisan political gesture. But there’s another way to look at the situation: By ensuring that Biden would get to appoint his replacement, Breyer could assuage somewhat the lingering grievance of Democrats about a “stolen” Supreme Court seat and make it less likely that a Biden nominee would face the same fate as Garland if Republicans regained control of the Senate in next year’s election.

A timely retirement by Breyer might also make it easier for Senate Democrats and Biden to reject the notion of expanding or “packing” the Supreme Court. In his Harvard lecture, Breyer said that those inclined to support court-packing or other structural changes should “think long and hard before they embody those changes in law.”

Breyer was appointed for life, and he has the right to remain on the court as long as he believes he can capably perform his duties. We believe that he may be somewhat in denial about the polarizing forces that have politicized the court since the 1980s, and that unilateral disarmament on the part of Democrats and Democratic-appointed justices won’t work. Nonetheless, Breyer should ask himself if stepping down now, after a long and distinguished career, wouldn’t ease rather than exacerbate a disturbing and unmistakable trend.