LETTER FROM WASHINGTON

Election day? More like a month

Barring a landslide, the count could drag on for weeks or longer

George W. Bush, the Republican, insisted he had won, charged that Democrats were trying to overturn a fair election and asked courts to stop recounts that showed him up by 537 votes out of nearly 6 million cast.

After 36 days of chaos, the Supreme Court agreed. They gave Bush the election by a vote of 5 to 4. The Democrat, Al Gore, conceded, and the constitutional crisis ended.

If this year’s contest between President Trump and Joe Biden ends in a photo finish, the consequences could be far more damaging to democracy.

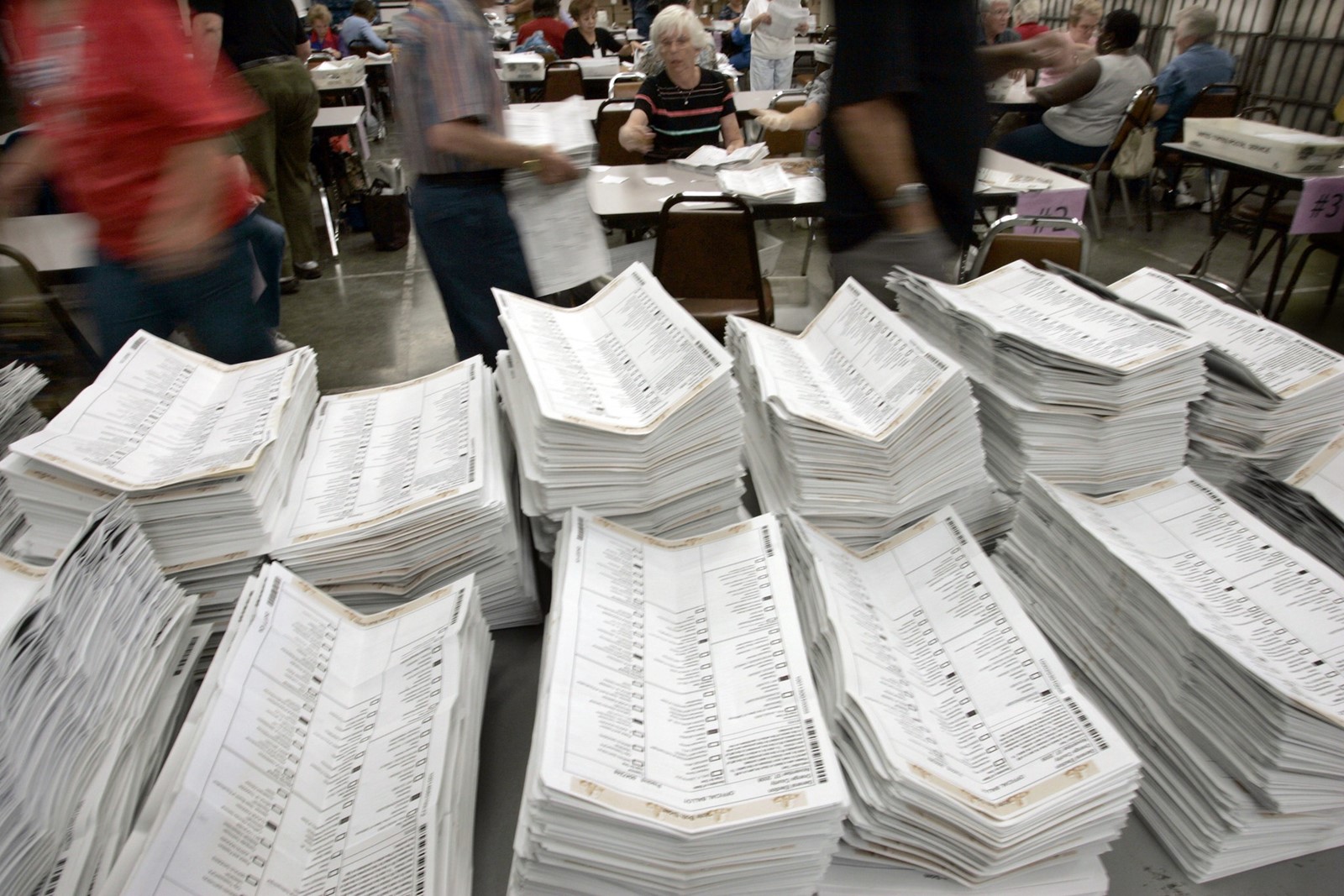

Tens of millions of Americans will try to vote by mail because of the COVID-19 pandemic. But officials in 14 states are prohibited from processing mail-in ballots until election day; counting them could take days or weeks.

Those states include Pennsylvania and Michigan, battlegrounds that could decide the election.

Here’s where it gets complicated. Since 2004, mail-in ballots have been disproportionately Democratic, a phenomenon known as the “blue shift.”

So, barring a landslide, we could see a “red mirage” on Nov. 3, an election night count of in-person votes that suggests that Trump has won — even though millions of votes for Biden are waiting to be tabulated.

At that point, three things are likely to happen.

Trump will declare victory, claiming (as he has before) that mail-in ballots are inherently fraudulent. Both sides will barrel into courtrooms, seeking to force states to decide the outcome their way. And demonstrators, some carrying weapons, will pour into the streets.

The president has spent months preparing his voters for fraud, although not a single vote has been cast.

“It’ll be fixed, it will be rigged,” he charged in July, without offering any evidence. “This is going to be the greatest election disaster in history.”

Biden has fired back, serving notice that he too can raise claims of misconduct. “This president is going to try to steal this election,” he said in June.

Election day? This is a recipe for election month — or months.

This summer, a bipartisan group called the Transition Integrity Project ran a series of war-game-style simulations, with former politicians role-playing the candidates.

Every close election scenario led to “the brink of catastrophe,” Rosa Brooks, a Georgetown University law professor and former Obama administration official, told me.

“These weren’t predictions; they were simulations,” she added. “The idea was that identifying the risks might be the best way to avert a disaster…. People are beginning to take this seriously, and that’s a good thing. But we’re probably not as prepared as we should be.”

Several factors worry her.

On election night, television networks could feel competitive pressure to declare a winner prematurely. Most important, Brooks said, is the Associated Press, the widely trusted news service that has acted in the past as a semi-official arbiter. Its decisions “have an outsize impact on perceptions,” she said.

The AP promises it won’t jump the gun.

“We’ve been seeing this coming,” David Scott, a deputy managing editor at the AP, told me. “We don’t call an apparent winner. We call a race when we’re confident that there’s a clear winner.”

State authorities could bungle their counts of mail-in ballots or be hampered by shortages of poll workers and funding.

Violence could force a halt to the vote count, and Trump could order troops into the streets. He could even order them to impound the ballots, helping his effort to stay in power.

“Biden can call a press conference,” Brooks said. “Trump can call in the 82nd Airborne.”

If an impasse persists long enough, Trump or Biden could call on state legislatures to ignore the popular vote and award their state’s electoral votes on their own authority, a power the Constitution gives them.

The battle probably would end in the Supreme Court or in Congress — but either way, it would leave the nation angrier and further divided.

There’s only one silver lining in these dire forecasts: We still have time to prepare.

It’s not only the candidates and the courts who will determine whether this election ends badly or well.

TV anchors and pundits must break election night habits and warn voters that a victor may not be known for weeks.

Voters should recognize the difference between groundless claims of fraud (like the charges Trump is already making) and the real thing.

Perhaps most important, leaders in both parties — Democrats if Biden loses; Republicans if Trump fails — must be ready to accept defeat and help their followers accept it too.

That goes especially for Republicans, whose vengeful candidate is behind in the polls but has already said he “cannot lose” if the election is fair.

Republican governors, members of Congress and state legislators could face demands to stop the count of mail-in ballots, award electoral votes to Trump and declare him the winner even if he’s impossibly behind in the popular vote.

In the end, it will be up to them to fulfill their deepest responsibilities — to not only the president who leads their party but to the Constitution, the voters and our shared democracy.