SCIENCE FILE

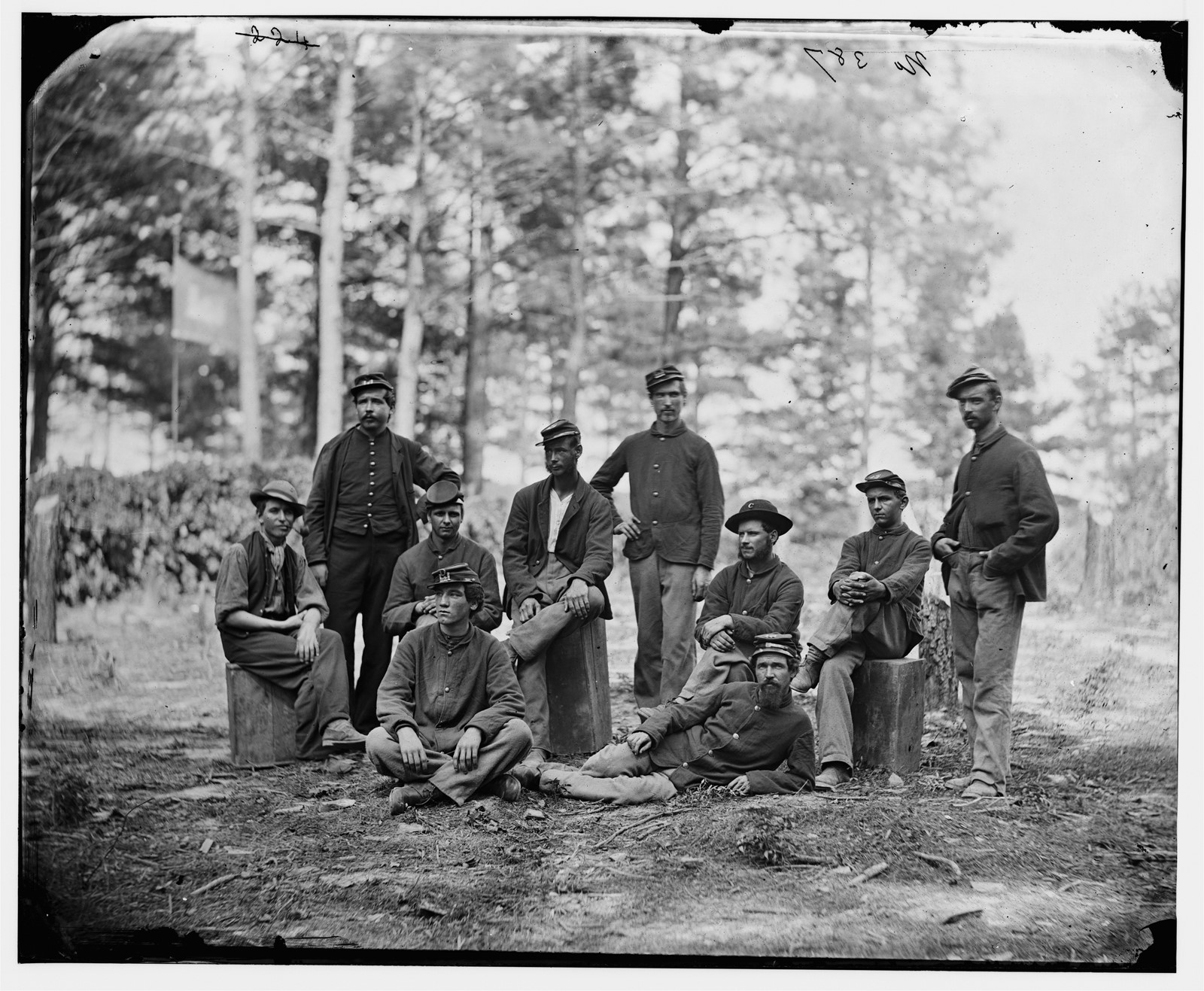

Long march of Civil War trauma

Research shows that sons of Union soldiers who had been POWs lived shorter lives.

An experience of life-threatening horrors surely scars the person who survives it. It also may have a corrosive effect on the longevity and health of that person’s children and, in some cases, on the well-being of generations beyond.

The latest evidence of trauma’s long shadow comes from the families of American Civil War veterans. Focused on the children of Union soldiers who were held in Confederate prisoner of war camps, it offers tantalizing clues about the means by which a legacy of misery is transmitted from parent to child — as well as a way to disrupt that inheritance.

After tracing the births and deaths of nearly 10,000 offspring of Union combatants, researchers found that the sons of men who served time as POWs lived shorter lives than the sons of men who were not held captive. They also lived much shorter lives than their brothers who were born before the war began, according to a study published this week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

UCLA economic historian Dora L. Costa inherited stewardship of a trove of Civil War service documents in 2013 after the death of her mentor, Nobel laureate Robert William Fogel. She had always assumed the records would tell a story of how education, class and economic differences influenced the adjustment of former soldiers and their families back to civilian life.

“I was wrong,” Costa said.

Instead, she found evidence to suggest that no matter how poor or prosperous his background, a father’s extreme hardship and privation alter the function of his genes in ways that can be passed on to his children.

In the annals of organized human suffering, the POW camps of the latter half of the Civil War rank way up there. For the first two years of the conflict, the North and the South held informal POW swaps. After the swaps ceased in 1863, desperation among Confederate commanders and indignation among leaders of the Union prompted both sides to deprive their prisoners of food, medicine, sanitation and shelter. As a result, hunger, overcrowding, cold and pestilence killed close to 16% of POWs from the North and 12% of POWs from the South.

The conditions at one of the most notorious Confederate prison camps — Andersonville in southwest Georgia — were particularly well-documented. Built for 10,000 people, Andersonville held more than 45,000 Union soldiers during the 14 months it operated, and 29% of them died of starvation and disease. The camp’s commandant, Capt. Henry Wirz, was tried and hanged after the Confederate surrender in April 1865.

The fates of the survivors who staggered north to resume their lives as husbands and fathers were also well-documented. And like many large groups of trauma victims studied by researchers, these veterans and their children told a powerful story.

Drawing on thousands of handwritten military and pension records preserved in the National Archives, as well as on U.S. Census data from the era, Costa’s team pieced together the fates of the children of Union soldiers who survived the war and lived at least until 1890.

The researchers identified offspring of 1,999 Union soldiers who were held as POWs — more than half of them at Andersonville — before returning home. They also found the children of 7,810 Union soldiers who survived the war without being captured by the South.

On average, Northern veterans who spent time in Confederate POW camps had 3.3 children, while those who avoided the camps had 3.1 children.

The differences between the two groups were stark — at least for the sons.

After reaching the age of 45 — old enough to see the effects of any inherited factors that might influence longevity — the sons of POWs were roughly 11% more likely to die at any given age than were the sons of men who had not been held prisoner.

In an even more telling comparison, the researchers turned up 342 POWs who had at least one son conceived before the war began and at least one more born after the war ended. The researchers found that, at any age after 45, the younger brothers were more than twice as likely to die than their older brothers had been when they were the same age. (With only 1,067 sons in this part of the analysis, the researchers said this finding should be interpreted with caution.)

The shorter life spans of the POWs’ sons didn’t become evident until they had reached what, in that period, would have been late middle age. Though death records were not uniformly detailed, these premature deaths were largely attributable to cerebral hemorrhages and cancer, the researchers reported.

The longevity gap remained after Costa and her colleagues accounted for a welter of socioeconomic factors that might drive differences in life span, such as family real-estate holdings and occupational class.

None of these patterns were evident among the daughters of the Union soldiers. That led the study authors to dismiss the idea that the psychological legacy of the POW camps could account for the differences. If a father’s trauma resulted in family violence, paternal absence or emotional distance, the effects would probably be seen in daughters as well as sons, they reasoned. And they weren’t.

The fact that sons, but not daughters, appeared to have inherited some life-shortening bit of their father’s misery does suggest that a genetic actor may be at work — one that is passed along with the Y chromosome, Costa said.

Epigenetics also might be at work here, she added. That’s the chemical signaling process by which genes turn on and off in different tissues at different times, often in response to environmental factors like food supply. While epigenetic marks don’t alter a person’s genetic code, they can profoundly alter how that code is expressed. And they appear to powerfully influence the expression of genes that are passed on to a growing embryo.

Consider the evidence from a series of studies tracking several generations in the isolated Swedish community of Overkalix, Costa said. That research has linked parents’ food availability to the midlife health of their children and grandchildren. Those studies’ complex findings have shown that dietary abundance or scarcity at specific points in time exert sharply different influences on men and women and their progeny. They’ve also furnished evidence that dietary stress may transmit certain vulnerabilities to future generations through paternal DNA.

Other studies of traumatized groups have found evidence that the experience turns genes on and off in ways that are carried down to the next generation and beyond.

In the nine months before the Allies defeated the Nazis in May 1945, Germany blocked all food supplies to the Dutch and caused a famine that killed 20,000 people in the Netherlands. Decades later, researchers would find that, in middle age, the children of Dutch women who were pregnant during that period — daughters especially — went on to suffer higher rates of heart disease, diabetes and schizophrenia. They also died earlier than their compatriots who were born before or after the famine. Six decades after their birth, the Dutch famine offspring still bore distinctive epigenetic signs of stress linked to poorer health.

Another study of Finnish children evacuated abruptly from their homes in the midst of World War II found that the daughters of evacuees were more than twice as likely to have been hospitalized for a mood disorder than were their female cousins whose mothers had not been evacuated. (There was no such relationship for sons.)

The new research on Civil War soldiers builds on this work by offering an intriguing bit of hope: evidence not only for the corrosive power of paternal stress, but also for the possible role of maternal nutrition in countering it.

The life-shortening effect of a father’s POW status was magnified for the sons who were born in April, May and June, when food supplies tended to be leanest. But that effect virtually disappeared among sons born during September, October and November, when harvests are in and food is typically more plentiful.

This disparity jibes with studies in animals that have shown the power of dietary supplementation before and during pregnancy to counter worrisome epigenetic effects, Costa said.

In an era when food is mostly plentiful, the lessons from an earlier America may not seem relevant, Costa acknowledged. But supporting the nutrition of childbearing women in communities under stress seems like a no-brainer, said Costa.

“Maternal nutrition seems like a safe and do-no-harm policy, and it is likely to have positive effects,” she said.