Amnesty to counter drug war?

Mexico’s presidential favorite says he might let some nonviolent criminals go free

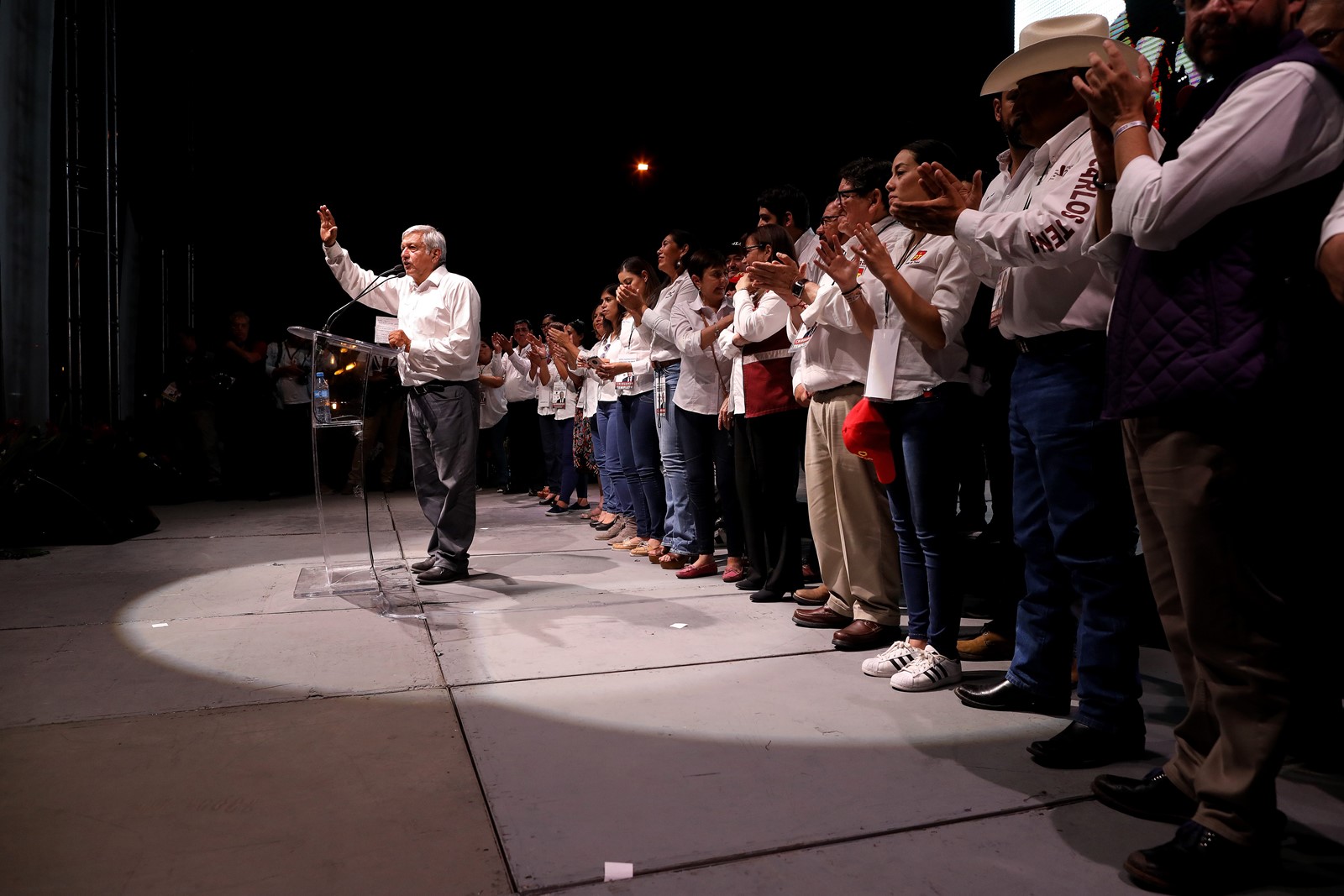

Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador, who has a wide lead in polls entering Sunday’s presidential election, has said that if he wins he may push for a law allowing some nonviolent criminals to walk free.

“I will not rule out any option” to achieve peace, he said at a recent debate.

Forgiveness for even low-level workers in the country’s multibillion-dollar drug industry would mark a dramatic shift from the militaristic approach that Mexico has long employed in its attempt to curb trafficking. With U.S. encouragement, Mexico has gone to war against the cartels, imprisoning drug users and drug runners, incinerating opium and marijuana fields, and sending thousands of armed soldiers into the streets.

Lopez Obrador, a left-leaning former mayor of Mexico City, is not telling Mexicans anything most don’t already believe when he says that strategy has been a failure.

The drug trade has grown — cultivation of poppies is up and Mexico has started manufacturing fentanyl and other synthetic drugs — and violence has exploded. More than 250,000 people have been killed and more than 30,000 have gone missing since then-President Felipe Calderon sent troops into the streets 12 years ago in an effort to neutralize drug cartels whose power was beginning to rival that of the state.

Last year, Mexico recorded more homicides than at any point in its modern history, and it is on track to break that record this year. Police and the military have been accused of grave human rights violations and of colluding with cartels.

Lopez Obrador has not proposed sending all troops back to their barracks. But at a recent campaign event in Chihuahua, a northern border state that has seen some of the worst violence, he advocated a more holistic approach to confronting drug trafficking, saying that Calderon had “converted the country into a cemetery.”

“You can’t put out fire with fire,” he said. “We don’t want militarization. We don’t want war.”

Lopez Obrador has said he would use economic development, job creation and educational opportunities to address the root causes of crime, giving federal scholarships to students and creating employment programs to keep vulnerable young people off the streets.

He has offered fewer details on the amnesty proposal, which he first mentioned in an offhand manner in December at an event in Guerrero state, one of the country’s top opium-producing regions.

His advisors acknowledged that it was a clumsy way to roll out such a controversial proposition. But they said it is something the campaign is seriously considering.

Amnesty, they said, would be part of a broader shift away from punitive measures and toward “transitional justice,” a term used to describe the way countries emerge from periods of conflict and address large-scale or systematic human rights violations.

Olga Sanchez Cordero, a retired Supreme Court judge who is expected to be named interior secretary if Lopez Obrador wins, recently told Reforma newspaper that the amnesty would be a “pacification strategy” that would shield some low-level criminals who grow, use and transport narcotics.

The effort, she said, would help reintegrate into society some of the estimated 600,000 Mexicans employed by drug cartels.

She said Lopez Obrador is also weighing decriminalizing drug consumption and launching a truth-and-reconciliation process. That undertaking, famously carried out in post-apartheid South Africa, involves the creation of a commission tasked with exposing past wrongdoing by a government or others.

Alfonso Durazo, whom Lopez Obrador plans to nominate as his secretary of public security, said at a recent forum on violence that the candidate “has proposed a process of peace and national reconciliation, not a pact with organized crime.”

He used the example of children as young as 8 or 10 known here as “hawks” because they serve as lookouts for older gang members. “Are we going to put young hawks in jail, or are we going to give them development opportunities?” Durazo said.

Jose Merino, another advisor, said the proposal is built on the idea that many people who perpetuate Mexico’s drug trade should also be considered victims.

“You have no money, so you get co-opted into crime,” he said. “You do things you’d never imagine yourself doing.”

The idea of an amnesty has divided voters, with a poll this year showing that more than 7 in 10 Mexicans rejected it. Jose Antonio Meade, the presidential candidate from the governing Institutional Revolutionary Party, told Lopez Obrador at a recent debate: “You want to forgive the unforgivable.”

Opponents also include the leaders of Mexico’s armed forces, with Naval Secretary Vidal Soberon warning late last year that it would make “the state complicit in crime.”

Skeptics question whether amnesty would lead to even greater impunity in Mexico, where government statistics show only about 7% of all crimes are properly investigated and about 2% result in convictions.

“I don’t know how you would apply it,” said Juan Manuel Andazola, the editor of El Diario, one of Chihuahua’s daily newspapers. “Who are you going to give amnesty to if you’re not even arresting people?”

The United States, which works closely with Mexican law enforcement in its fight against drug cartels, is weary of a softening of Mexico’s security policies.

U.S. officials believe Mexico’s best bet for reducing violence is strengthening its institutions.

Each year, the U.S. Congress appropriates about $100 million for the Merida Initiative, a bilateral partnership forged in 2007 to help reduce the power of drug trafficking in Mexico. That money has been used to help train police, prosecutors and judges, fund improvements of prisons and jails, and aid an ongoing overhaul of the criminal justice system.

The amnesty proposal has support of many human rights advocates, who have been critical of the drug war.

“There hasn’t been a reduction in violence, and it hasn’t reduced drug production,” said Jose Antonio Guevara Bermudez, director of the nonprofit Mexican Commission for the Defense and Promotion of Human Rights. His group recently called on the International Criminal Court to investigate atrocities allegedly committed by the Mexican military during an anti-drug offensive in Chihuahua.

“Without a doubt it has to change,” he said. “It’s a prerequisite for the country to achieve peace.”

Amnesty is not unprecedented in Mexico, which in 1978 offered it to government-opposition activists prosecuted during the country’s so-called dirty war and again in 1994 to Zapatista rebels.

But Maureen Meyer, a Mexico expert with the think tank Washington Office on Latin America, said that to reduce violence an amnesty would need to be paired with serious anti-corruption efforts and improvements to the justice system, including the establishment of a strong, autonomous national prosecutor’s office to stop political meddling in criminal investigations.

“Amnesty needs to be accompanied by reform,” she said.

The proposal has been most controversial among one constituency: relatives of the dead and the missing.

After Lopez Obrador announced his plan last year, some victims groups came out in opposition. But others say they support it.

Lourdes Hernandez, 53, believes an amnesty and truth commission could help solve the 2010 disappearance of her daughter because it might encourage the perpetrators to talk.

Her daughter Pamela Portillo, 23 at the time, was stopped at a police checkpoint in Chihuahua by an off-duty soldier and never heard from again.

Hernandez sold her house and car to fund a desperate and dangerous quest to find her daughter. Eight years later, she is still looking.

Based on her conversations with soldiers and criminals, she has come to believe that the off-duty soldier had been working on the side for two competing drug gangs.

If her daughter is dead and buried, her mother would like to know where.

“The only thing I want now is the truth,” she said. “I want that more than punishment.”