It was ‘Google before Google’

On the inside cover of Barbara Ward’s “Spaceship Earth,” Stewart Brand wrote: “What I’m visualizing is an Access Mobile with all manner of access materials + advice for sale cheap. Including dandy survival and camping equipment, catalogs, design plans, periodical subscriptions, copy equipment (+ other gathering equipment - some element of barter here). Prime item of course would be the catalog.”

As an afterthought, in a riff on a then-popular backpacking catalog with a cult following, he added: “Notion: every catalog item pictured is held by a naked lady.”

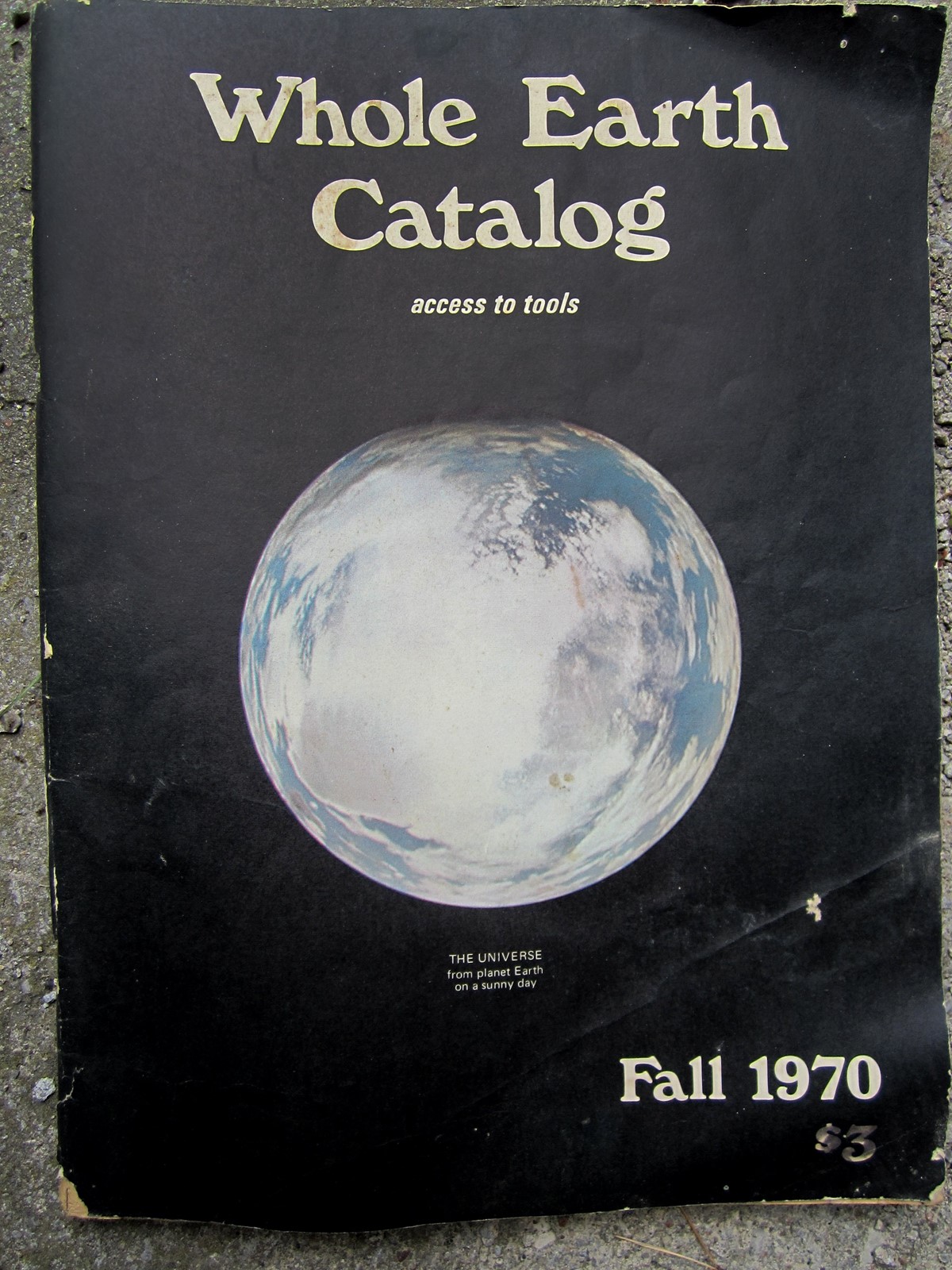

The ladies never materialized and the truck quickly faded, but half a year later the first Whole Earth Catalog was published and Brand’s handwritten business plan exploded as an overnight national bestseller that would ultimately sell more than 2 million copies and, in 1972, win the National Book Award.

It would also help define a generation who, alienated by the Vietnam War and a materialistic nation that seemed to have lost its soul, was forming a powerful counterculture.

There had never been anything quite like the catalog.

Subtitled “Access to Tools,” the first 64-page volume sold for $5 and included photos, drawings and short written endorsements of books, tools, gadgets and materials organized into seven sections ranging from “Understanding Whole Systems” and “Shelter and Land Use” to “Nomadics” and “Learning.”

Decades later, in 2005, when Apple co-founder Steve Jobs tried to explain the catalog to a new generation in a Stanford University commencement address, he described it as Google before Google.

However, that doesn’t quite capture the spirit or the intent of Brand’s riotous assembly of notions and revelations, large and small. Using a search engine is akin to taking a rapid trip down a long hall to find what you are hunting behind a door. In contrast, the Whole Earth Catalog was like a seemingly endless hall of adjacent doors — all open, easy to peek into.

The Whole Earth Catalog was serendipity between covers.

That was underscored when, in June 1971, Brand commissioned novelist Gurney Norman to write “Divine Right’s Trip” and then threaded it in easily consumable chunks through the Last Whole Earth Catalog — in the process drawing readers to parts of that sprawling 452-page edition they wouldn’t have otherwise visited.

Leafing through the Whole Earth Catalog would take you from a description of a textbook on engineering design to the Thomas Register of American Manufacturers to a summary of a New Scientist article raising the question, “Should sportsmen take dope?” and then to a half-page illustrated description of a book on “Creative Glass Blowing.”

The catalog resonated with a generation who had grown up in an upwardly mobile but stale society. Millions of them would explore “sustainable” living in the form of the brief back-to-the-land movement. Others dabbled in the human potential movement and psychedelic drugs. The catalog became both groups’ bible of transformation.

Jamis MacNiven, who later founded Buck’s of Woodside, a legendary Silicon Valley cafe, came upon the Whole Earth Catalog while he was living in Connecticut. With his wife, he pulled up stakes and moved to the hills behind Stanford University, where they lived off the grid on 40 acres.

Steffi Czerny, now a managing director for the Burda Publishing empire in Germany, discovered the catalog in the 1970s and was inspired to roam by Greyhound bus among communes from Vermont to Colorado to Tennessee.

Alan Kay, a young Xerox computer scientist credited with conceiving the modern personal computer in 1968, herded the corporation’s librarian over to the Whole Earth Truck Store in Menlo Park and persuaded her to order all the books on display for the company’s Palo Alto Research Center. The catalog was an inspiration for the kind of access to information his Dynabook computer idea would enable, Kay recalled.

The half-decade that led to the catalog was remarkably creative for Brand. Before he enlisted, he studied biology at Stanford, and after the Army he took up with poets and artists, including Ken Kesey and his Merry Pranksters. In 1964, Brand produced a multimedia slide show called “America Needs Indians.” In January 1966, he organized the Trips Festival, a San Francisco “happening” that led directly to Haight-Ashbury and the Summer of Love. Later that year, he launched a personal crusade asking “Why Haven’t We Seen a Photograph of the Whole Earth Yet?” Many believe he persuaded NASA to make its shot-from-space photos publicly available, which in turn helped jump-start the Save the Earth ecology movement of the 1970s (and provided the name and cover image for the catalog).

Art Kleiner, editor in chief of Strategy+Business, who worked at CoEvolution Quarterly, a follow-on to the catalog, pegs Brand’s contribution as not just providing people with access to tools, but also instilling in them a deep faith in human progress. “It was the idea, ‘Let’s take this baby, humanity, out on the road and see what it will do,’” he said.

Now half a century after the publication of the first Whole Earth Catalog, Brand has remained consistently ahead of the curve. The 79-year-old and his wife, Ryan Phelan, have founded an effort to use genetic engineering to rescue endangered species facing climate change.

The catalog’s opening sentence still applies: “We are as Gods,” it reads, “and we might as well get good at it.”